|

| |

|

| Orientalism

is a masterpiece of comparative literature studies and deconstruction, published

in 1978 it is arguably Said's most rigorous piece but undoubtedly his most influential.

This is a examination of the academic discipline of Oriental Studies, which has

a long history most of the European universities. Oriental Studies is a pastiche

areas of study which include philology, linguistics, ethnography, and the interpretation

of culture through the discovery, recovery, compilation, and translation of Oriental

texts. Said makes it clear that he is not breaking new ground. Said limits Orientalism

on how English, French, and American scholars have approached the Arab societies

of North Africa and the Middle East. Although at times he refers to other periods

- ranging as far back as the Greeks, the ttime period he covers is more limited

than the scholarly field really extend. Said stays within the confines of the

late eighteenth century to the present, whereas European scholarship on the Orient

dates back to the High Middle Ages. Within his time frame, however, Said extends

his examination beyond the works of recognized Orientalist academics to take in

literature, journalism, travel books, and religious and philosophical studies

to produce a broadly historical and anthropological perspective incorporating

Foucaultian notions of "Discourse" and Gramscian notions of "Inventories". His

book makes three major claims. Firstly, that Orientalism, although purporting

to be an objective, disinterested, and rather esoteric field, in fact functioned

to serve political ends. Next, his second claim is that Orientalism helped define

a European (mainly English and French) self-image. Lastly, Said argues that Orientalism

has produced a false description of Arabs and Islamic culture. Whether you agree

with him or not, feel that he may have misappropriated Foucault or feel like I

do that what he is putting out is not comprehensive enough therefore is suspect,

the point is moot. What is important is that Said has opened up a whole new area

of discussion. The book has brought the author a sense of academic place and the

author has placed a sense of notoriety on the subject. Trapped in what Foucault

has described as an "Authorial Function" of book and author, author and book,

the book is a reawakening and sin to overlook. |

| A

timeless book, Said brings to presence the subject of Palestine. First published

in 1977, this unique and deeply insightful work - according to the book cover

- made Palestine the subject of serious deebate. The crisis is no less real now

that it was in 1977, and this book can shed some light on understanding the fundamental

underlying issues. In this book, Said tries to form a new understanding by tracing

the roots of the Palestinian question. Said, in this pivotal work, examines such

things as the Israeli invasion of Lebanon, the intifada, the Gulf War, and the

ongoing Middle East peace process. It is usually helpful to take step back to

consider where we came from to ascertain where we are going. Like the cover says

- and I agree - "For anyone interested in this region and its future, "The Question

of Palestine" remains the most useful and authoritative account available". A

book to read, ponder and reread. |

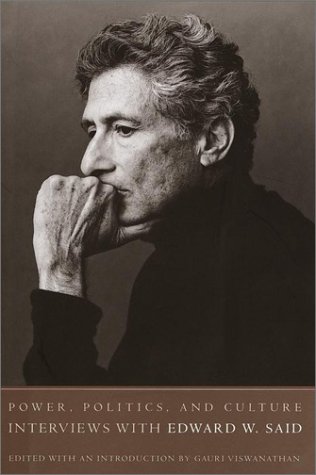

| By

far the best informed and most complete review of Edward Said and his thoughts

that I have come across to date. Ashcroft and Ahluwalia take the time to explain

all the background information that is absent in most introductory books.

This volume take great pains to explains Said's

key concepts, ideas, contexts and impact. Both authors take the time to address

reference to both his scholarship and journalism. The range of ideas include:

(1)the function and space of text and critic in "the world", (2)Power/Knowledge,

(3)the social construction of the "Other," (4)the joins between culture

and imperialism, (5)exile, (6)identity, and (7)Palestine. It

needs less explanation from me and more engagement from the reader to get the

fullness of the experience. What is key is how well they have taken the time to

explain through most of Said's interlocutors such as Dennis Porter, Aijiz Ahmad

and Robert Young - to name a few. The key is to keep in mind the critique of Said

and how fair and relevant they are. Said's use of Foucault is problematic and

is discussed and certainly well explored in this book. Buy it, read it and digest

it - then re read Orientalism. |

|

Said's work is complex, intertextual and far reaching.

Barsamian's interviews are a enlightening yet they are an incomplete portal to

the work and impact of Edward Said. Don't get me wrong, the conversations with

David Barsamian squarely place Said as a player in an often oversimplified discussion

of a very complex issue - Palestine.

One of the more controversial, yet not

often discussed topics is the role of the PLO in general and Arafat's in particular

to the future of Palestine. The role of Arafat is not to be underestimated - he

has singlehandedly represented (or at least singlehandedly represented himself

as the voice of a nation) the interests of the Palestinian Arab. What are we to

do with Arafat? More importantly, what at the disparate Palestinian Arabs going

to do about Arafat? That is one of the key questions Barsamian and Said takes

up here. If an organization that was built on "Liberation" is involved

in Administration - is it a good thing? Are the players in this case qualified

to perform Administration? If not, should others be considered to carry the banner.

Ironically, you can draw a metaphor here that is patently Jewish. Moses did the

liberation but Joshua took the Jews to the "promised land" - mind you,

I am not making any comparisons of Arafat to Moses or the notion of the "promised

land" as 100% legitimate - I am merely agreeing with Said that a second look

might be advantageous.

One of the major points is the notion that there will

never be normalization of relations unless the relationship is a relationship

of equals: "We are now on a new stage. What the Israelis want is a normalization

of relatiohips between Israeland the Arab states including the Palestinians. Of

course I'm all for normalization. But I think real normalization can only come

between equals. You have to be able to discriminate between tutelage and dependency

on teh one hand and independence and standing up as a co-equal with your interlocutor.

We haven't done that. That's why I think it's the most important political task

for the coming decade." p. 167. |

| | |  | The

Prize : The Epic Quest for Oil, Money & Power by Daniel Yergin: It

was worth all 877 pages. I have yet to find so comprehensive a book that explores

the ever so complicated world as that spun around Oil. I found myself unable to

put it down. According to Daniel Yergin, "Petroleum remains the motive force

of industrial society and the lifeblood of the civilization that it helped to

create." In an effort to drive his point home, Yergin sounds as if everything

revolved around Oil. Judging from the extensive research he did one would almost

think it did (or does). Yergin might be accused of totalizing the issue but I

don't think he does that or even means to do it here. He certainly does not other

elements/forces that motivate man and in fact even incorporates them. But his

thesis and interest is Oil and for that he won a much deserved Pultizer Prize.

I found Yergin's book to be an explanatory one. According to Yergin, the prime

motive of the early American oilmen was greed. He writes that their "merciless

methods and unbridled lust" nevertheless "turned an agrarian republic

. . . into the world's greatest industrial power." Yergin is evenhanded about

the motives, interests, rights, and pride of the Latin Americans, Arabs, and Persians

who have had the questionable luck of sitting on most of the oil and who have

long been dealing with the British, the Dutch, and the Americans who want to market

and control it. Oil defines the 20th century. This is a huge claim, which Yergin

makes. The Prize undeniably is worth buying, having, and discussing. The book

is extensive and heavily researched and chronicles the development of the Oil

industry from its inception to the development of OPEC and the eventual price

stabilization of the 1980s. Yergin also deftly articulates the development of

the usual suspects: Standard Oil, Shell, Gulf, Royal Dutch, etc. Moreover he goes

into extensive detail about wild-catters and independents. We are introduced to

several enigmatic individuals ranging from John D. Rockefeller to William F. Buckley,

Sr., and Armand Hammer. We are transported to the yacht of Sheik Yamani and to

the home of a young Col. Qaddafi. We are there are those responsible are setting

the stage for the rise of OPEC and we experience how the member states navigate

through their various issues and agendas. I was especially intrigued by the treatment

of Mossadegh, the Shah Reza Pahlevi, and Saddam Hussein. Yergin sensitively considers

how important oil is, nor is he surprised when deceitfulness and brutality are

used against those who won't play ball, as in Iran to bring Mossadegh down, or

in Kuwait to get Saddam out. Yergin's realism makes explicit that not only the

West and Japan, but also those close to him, could never have afforded to trust

Saddam with his Oil reserves. Did he sensationalize? Perhaps. However, for all

the time spent reading the book I can only sing praises to a book that has enhance

my understanding of the Middle East and beyond. Is there a PBS series that spun

out of this book? If not, there should be. |  | No

god but God : The Origins, Evolution, and Future of Islam: I have to thank

Reza Aslan for taking my understanding of Islam to a different level. Perhaps

the best book of its kind - I highly recommend it to anyone interested in the

Middle East and Islamic studies... particularly in terms of opening up new spaces

of consideration. Steeped in the 'Clash of Civilizations' offerings that I am

used to (what with reading Bernard Lewis' 'What went wrong?: Western impact and

Middle Eastern response,' Samuel Huntington's 'The Clash of Civilizations' and

Francis Fukuyama's 'The End of History and the Last Man' - all available on Amazon.com)

Aslan's angles are a breath of fresh air.

Prior to reading Aslan's 'No god

but God : The Origins, Evolution, and Future of Islam,' I began one of my paper

on Islam in the Philippines with "The Philippines is perhaps the most enigmatic

country in Southeast Asia - a curious mix of Islam and Catholicism tenuously co-existing

in a milieu of misunderstanding and fear.' I ended the same paper with 'If one

takes into account common sense understanding or the "Lewis doctrine"

(Hirsh, Michael. "Misreading Islam." AlterNet: Misreading Islam. 12

Nov 2004. AlterNet. 12 Nov 2004 <http://www.alternet.org/story/20488> 1),

which according to Hirsh is, "Lewis's basic premise, put forward in a series

of articles, talks, and best selling books is, that the West - what used to be

known as Christendom - is now in the last stages of a centuries-old struggle for

dominance and prestige with Islamic civilization. (Lewis coined the term "clash

of civilizations," using it in a 1990 essay titled "The Roots of Muslim

Rage," and Samuel Huntington admits he picked it up from him) (Hirsh 2) one

could be easily convinced to, once again to borrow from Hirsh, end up `Misreading

Islam.' "

If one aligns oneself with likes of Fukuyama, Huntington, and

Lewis, one could very well see the development in southern Philippines as part

of an unreflective and unsophisticated "clash of civilization" and effect

policy under assumed preconceived notions about Islam in general, and the situation

in Southeast Asia and the Philippines in particular.

However, if one aligns

oneself with Lewis's detractors like Edward Said (Hirsh 3) then one could well

see Lewis's conclusions to be cavalier (Hirsh 3), staid and unreflective and therefore

perceptions, decisions, and policy relating Islam in all its manifestations, dangerous

at the least and antagonistic at worse.

Taking the theoretical "clash

of civilization" into consideration one is left thinking that perhaps, yes,

it has some explanatory powers but positions like Lewis's cannot fully explain

the reality on the ground, hence the need for studies such as Aslan's. We need

to take into consideration Aslan's contrasting but promising:

'Despite the

tragedy of September 11 and the subsequent terrorist acts against Western targets

throughout the world, despite the clash-of-monotheisms reality underlying it,

despite the blatant religious rhetoric resonating throughout the halls of government,

there is one thing that cannot be overemphasized. What is taking place now in

the Muslim world is an internal conflict between Muslims, not an external battle

between Islam and the West. The West is merely a bystander - an unwary yet complicit

casualty of a rivalry that is raging in Islam over who will write the next chapter

in its story.'

Reza Aslan's `No god but God: The Origins, Evolution, and Future

of Islam' is a very promising book in terms of possible consideration for and

by the Islamic world and the world in general. Written with nuance, class, and

insight, I give it a resounding 5 stars. | |

| What

Went Wrong? : The Clash Between Islam and Modernity in the Middle East by Bernard

Lewis: If what Bernard Lewis penned in

this book is entirely accurate, the real question facing all of us at this junction

is the distinction between `westernization' and `modernization.' Not to seem like

an apologist for Islam, but the question beyond Lewis's challenge to the Islamic

world to re-examine what it rejected - and ask why not effect change? `What Went

Wrong?" brought to presence to me a different response to a challenge...

not better or worse, just different. Lewis admittedly is brilliant as he lays

out his historiography and asks Muslims to re-examine the basic query: What went

wrong?

How did such an envied, dominant

and culturally rich society find itself exposed to Western imperialism? According

to Lewis, the rejection of modernization (at this junction in the review a synonym

westernization) resulting in a shrinking inward by the Islamic cultures inclusive

of countries such as Turkey, Persia, and Arabia. Lewis's sweep of Islamic history

tries to get at the core of what he sees as the quandary that the response to

the western challenge according to him is predictable. Such notables as Edward

Said and Albert Hourani see such a sweeping discourse as problematic. According

to Lewis, the Islamic world became too self-absorbed and oblivious to ideas for

useful change. In contrast to countries in East Asia - particularly Japan - who

reacted differently to what seemed like an inevitable cultural encroachment -

well the results are self-evident. To borrow from Lewis, clerics and rulers on

the premise that modernization was westernization resisted restructuring and reform.

As the West came to presence, the Islamic world saw little of value in westernizing

and was leery that Western values would replace it. It can't really be called

pure conservativism as Japan embraced the challenge of western influence - seeing

its inevitability - but the Islamic world decided to stay with what was tried

tested and true. Japan took from what it saw as the best in the west and made

their own.

The challenge that Lewis posits

beyond the "blame game," centering on "Who did this to us?"

includes a host of players such as Mongols and of late to the Americans for their

cultural and economic hegemony. While yes, blaming may uncover the issue of what

went wrong (and this is a question all regions need to ask themselves...) Lewis

brazenly asks Muslims to move beyond the blame game to a more productive: "How

can we fix the problems we have?" To effect change does not have to mean

that you are modernizing, per se or westernizing, per se. To effect structural

and cultural change to allow people to have the freedoms to develop and question

is not purely a western thing - therefore changed should not be feared, it should

be embraced. The thing is, the world will move along without us... and it is.

There is, admittedly, much to be leery about by relying on technology - but there

is much that can be gained by carefully changing one's quality of life. Far be

it for me to suggest such places as Singapore or Japan - which have embraced the

challenge and responded - enjoy the fruits as well as ills of so called modernization.

Lewis brazenly suggests a need to somewhat grab the bull by the horns of Western

democracy, and like so-called `western' values and that the enemy may be less

external and is really internal.

I have

to give Bernard Lewis kudos for asking the hard questions about what needs to

be done. The truth is, as previously mentioned, all societies need to constantly

to rearticulate, reinvent and reinvigorate themselves. Sometimes it is easier

from the outside looking in as one is not as `invested' in the reification of

the status quo. All cultural sensitivity issues taken into consideration, re-evaluation

should be seen as an opportunity for growth rather than a tenacious clinging to

a past that has been somewhat constricting. That Lewis's work is provocative and

a major contribution to Islamic studies is beyond question. What scholars need

to do now is to test the veracity and theoretical framework (not to mention historiographic

detail). The findings and suggestions are not meant to provoke and should be taken

in the spirit within which it was written. It does not answer all but it certainly

answers some of the issues facing the Middle East and on that note all of us. |

| | History

of the Arab Peoples by Albert H. Hourani: To

those who have had their history lesson from Hollywood, it is easy to see the

"creation" of the Arab world centering around T. E. Lawrence and the

Saudis. However, books like Albert Hourani's A History of the Arab Peoples offer

a counterpoint. Beautifully written, in plain and simple English, this book is

comparable to those that have come before. It serves to broaden our perspective

around the richness that is the Arab world. The range of the book is amazing -

pre-islamic empires, social constructions, religion, civilization. Without the

hyperbole that marks works that wish to compensate for the lack of information

about what has gone before, Hourani takes us to a time and place we have never

seen. OK, there are parts that seem more academic than your average book but it

gets to the point. Richly detailed and very detached, the world is richer for

books like this. |  | JOURNEY

OF IBN FATTOUMA, THE by NAGUIB MAHFOUZA:

counter epic, the story centers around the "there" but not the "back

again". As I read it, when Ibn Fattouma goes from place to place in search

of Gebel, he learns all sorts of things - mostly tolerance. Sure all the places

seem like a what would could be modern day places, it boils down to Ibn Fattouma

trying to find that all illusive "Heaven" or "Nirvana" or

"Shangri-La" - What is the true illusion? That it does not exist? maybe.

Anyway, his experiences with Arousa is a wonderful metaphor as the everyman. Places

like Mashriq, Haira, Halba, Aman and Ghuroub we get a chance to see outrselves

and the ridiculous ways that we organize ourselves. In short, it is a story of

discovery. It makes me think of the futility of a search for that perfect place.

Where does he center his perfect place? Guess you will just have to reaqd the

book. it is the only piece of Mahfouz that I have read and I am not surprised

to learn that he was awarded a Nobel Prize. | | | |

| | |

| | Hideous

Kinky (1999): One of the most refreshing "desert" movies I have

seen in a long time. It does stretch one's ideas about a single mother running

around the desert with two children and being that safe everywhere she goes. This

Gillies MacKinnon movie about a single mother (Kate Winslet) and her identity-seeking

hiatus around Morocco in the hippie days of the early 1970s, moves along the path

most taken: a soul-searching trip to an idealized Orient. Hideous Kinky is loosely

based on Esther Freud's novel. I'm certain that the experience was real enough

for her but it really misses on a few key safety issues of modern day travel.

Kate Winslet is wonderful (and her two young co-stars are adorable) and comes

back with much more than dust in her sandals - she is transformed. Westerners

who take these soul searching trips to exotic lands themed stories gives cinematographers

license go to town. The old world landmarks are wonderful and the old men whose

silences speak volumes is pure Orientalism (see Edward Said's "Orientalism"

also available on Amazon.com). Those romantic dusty landscapes at sunrise are

sure to draw in the desert lovers like myself. The ruins, the mosques, the Bedouin

tent, all giving off a sense of ancient mystery. Is it really just "Orientalism"?

Things is, it beats "The Sheltering Sky" with its rustic charm and light

manner. The outward portion of the story is great but it betrays a deeper, more

soulful deliberation. Stories like this are meant to be an "inward odysseys",

in which the protagonist releases torments that are alive and well "at home"

- and that is the crux - there is a ";home." Bea (Bella Riza) and Lucy

(Carrie Mullan) and the mother to Julia (Winslet), revels in Marrakech together

with Bilal (Said Taghmaoui), who becomes Julia's lover. "Hideous Kinky"

is a pastiche of "episodes" leaving us to imagine or figure out for

ourselves the internal changes. The phrase "hideous kinky" is not a

teaser but a catch all phrase by two young ones that could mean absolutely anything.

Watch it with a tinge of cynicism - since the beauty of the landscape, the children

and the promise of liberation are all seductive. Is it all "Orientalism"? |

|

Osama DVD ~ Marina Golbahari: In

the opening scene of Osama we see a group of rebelling women marching down a dusty

road for the rights of women to work. As was allegedly under Taliban custom, women

were not permitted to work outside of the home. In Osama, for one young girl in

particular and her family this meant starvation. With few (or no) options, her

mother and grandmother cut her hair and dressed her up to appear like a boy, giving

her the freedom to find work, and certainly the movie lent itself to depicting

an acute sense of fear over her being exposed. In Osama we see images - that would

understandably appear to us as a bankrupt way of. Even if this movie had just

a modicum of truth, prejudice and intolerance becomes all the more frightening.

One gets the sense watching Osama that this is, understandably, a one sided film.

As viewers, we need understand our role to assess the actual veracity of the depictions.

If the movie has but a modicum of truth, as mentioned previously, then it has

succeeded in showing us the darker side of the human condition.. One of the most

startling portrayals certainly is the filmmakers/writers sense of the treatment

of women. The sense one gets is that the primary aim of Osama is to illustrate

how women are oppressed and not to communicate the fullness of a life - or the

totality of their experience - and it could also be argued that in Afghanistan

there is (or was) a lack thereof. As with most movies of this genre Osama is meant

to afflict the comfortable and comfort the afflicted. We need to ask this question

when watching movies of this sort: Is this film about an honest depictions of

a way of life that for a lot of women is about repression, derision, and the suffocating

two-facedness of their male counterparts? This is not a film that was meant to

rekindle memories of pastoral days or walks down the beach, and although it has

been informative in illustrating some of the realities it seeks to portray, it

earnestly attempts to open viewer's eyes to the condition of a people who up until

recently `outsiders' have not been privy to. The film is sold as a "true

story," and while some may split hairs about just how honest the filmmakers

are (and they would be right in being cynical about this `mocumentary'), there

is no questioning some of the disturbing realism and it should be disturbing.

We straddle the difficult divide watching movies of this kind - that of it being

a fictional depiction, on the one hand, and an attempt to portray a reality on

the other. The viewer is left with the responsibility to decipher fact from fiction,

truth from sensationalism. The viewer should, in the end, have, at least, the

ability to understand the duality of `fully human' versus man's ability and propensity

to abuse power. That Osama is thought provoking is beyond doubt. That it is completely

factual is understandably suspect to those who provide checks and balances. We

all need to be cautious of unreflective acceptance in any case no mater which

side of the fence one sits - even if you set up the problematic as such. In the

end, we are left with one human being looking to develop to one's fullest potential

and the discourse of power meant to deprive it/her of the same. We should walk

away form this, not with an intolerant sense about one culture but the very real

sense that power can and is abused - and that it should be questioned and in most

cases opposed. If Director Siddiq Barmak is to leave us with one impression lasting

- at least let it be that. Watch it and juudge for yourself. |

Edward

Said and Terrorism

An Interdisciplinary reading in the exploration of the

"Other"

Copyright

© 2001 Miguel B. Llora, MA. All Rights Reserved. The

Interdisciplinary approach has been tremendous. Engaging Said along the lines

of film has allowed me to analyze Orientalist representation from a sociological

as well as historical perspective. Juxtaposing Lawrence of Arabia and Exodus gives

you sense of the Other from a very creative perspective - historical and film

depictions. Film and

History

The movie Lawrence of Arabia is all about T. E. Lawrence.

So? Well, the result is a movie centered on the discourse of what Edward Said

has defined as "Orientalism". If you re-watch and re-examine the movie within

the framework or Orientalism taking into account such things as the representation

of the Arab as the Other, T.E. Lawrence as the Agent for the creation of the Arab

identity, the horde depictions, the lack of ability to articulate on their own,

the all important negative representation of the Turks the picture will take on

a new meaning. Let us examine each topic one by one.

The pivotal character

of Auda abu Tayi (Anthony Quinn), with such memorable lines as:

Auda Abu Tayi:

I am Auda Abu Tayi! Does Auda Serve!

Crowd: No!

Auda Abu Tayi: Does Auda

Abu Tayi serve!

Crowd: No!

Auda Abu Tayi: [to Lawrence] I carry twenty-three

great wounds all got in battle. Seventy-five men have I killed with my own hands

in battle. I scatter, I burn my enemies' tents. I take away their flocks and herds.

The Turks pay me a golden treasure, yet I am poor! Because *I* am a river to my

people!

Lawrence: My friends, we have been foolish. Auda will not come to

Aqaba. Not for money...

Auda Abu Tayi: No.

Lawrence: ...for Feisal...

Auda Abu Tayi: No!

Lawrence: ...nor to drive away the Turks. He will come...

because it is his pleasure.

[Pause]

Auda Abu Tayi: Thy mother mated with

a scorpion.

What do we read? I read that Auda is in effect the representative

Arab leader (purposely placing aside the Sherif Ali role played by Omar Sharif)

who is a shallow tribal overlord whose primary motivation is money, who leads

a band of faceless and greedy Arabs. Despite the claims to the contrary, Auda

does not come "for his pleasure" but for the promised gold. Later, upon realization

that Lawrence had duped him, Auda proceeds to make a new agreement with the same

on the promise - but this time with English gold. Does this really give the Arab

agency? No. Is the Subaltern speaking here? No. Is this Bolt and Lean restructuring

and confirmation of Arab stereotypes. Absolutely. What were they thinking? Another

curious aspect of the movie is that Lawrence is the only agency the "Arabs" (a

notion which he single-handedly creates) and is the prime mover - no, the only

mover. The movie plays out yet another dangerous stereotype of the Arab who cannot

think, create, nor motivate himself - they need Lawrence. The Arab needs outside

agency to create himself. Don't you find that just a bit ironic? If this was your

only encounter with the Arab world you will have hitherto been convinced that

the Arab is motivated solely by money and cannot articulate the creation of a

state - much less even cares about it.

The depictions of the Arabs on Camels

and the horde of mercenaries will linger as the dangerous and mysterious Arab

and he is beginning to be unmasked. However, this chimera and those I mentioned

above serve to reinforce false stereotypes and leaves the Arab as the Other. Lean

and Bolt try to effect an out through the characterization of Feisal as the Same:

Prince Feisal: Young men make wars and the virtues of war are the virtues

of young men: courage and hope for the future. Then old men make the peace, and

the vices of peace are the vices of old men: mistrust and caution.

However,

he is always remote, always aloof and always between his elite guard of black

clad Bedouin. Mysterious, always mystery. It does not work.

What in effect

David Lean has accomplished is a classic of modern cinema shrouded in seductive

of the mysterious Orient, in epic scale and proportion coupled with music to accompany

the grandeur -- what we are really left with is the dehumanizing of the Arab and

the escalation of T. E. Lawrence to the status of Messiah.

What about

the encounter of Lawrence of the Turks - what message did that leave you with?

If anyone is really a victim in this movie it is not the Arabs but the Turks.

Are they lurking about as is suggested with homoerotic suggestion and potential

for violence? What about Turkish complexity, culture and agency? Lean could have

placed a counter to this representation or left it out altogether.

The

object is not to finger point as that leaves us within the framework of colonialism

and further away from a much-needed liberation. We can take up the unfinished

project of Frantz Fanon, move away from the politics of blame to a politics of

liberation - but only through analysis. As much as was I was seduced by the movie

for the longest time, a revisit has allowed me to gain perspective and see it

thus. All this however, does not detract from the great cinematography and does

not detract from its greatness and that is its greatest weakness. What

about Exodus? Exodus is a triumph of cinema and never did it bore this viewer

in its entire run. However, there is a problematic. The movie is one sided and

despite the courageous depiction of John Derek as Taha - it did not go far to

give a sense of the complexity of this issue from a Palestinian Arab perspective.

What is key here is to take into account the Jew as the Same? While all Arabs

(Semites) in Lawrence of Arabia are dark, the Jew (Paul Newman, etc.) is white.

I will assume for historical accuracy that the Jews on the "Star of David" are

Ashkenazi and are of European origin. The key though is to view the Jew as the

Same and to see his struggle from one side and despite small references to the

Arab, the Arab has suddenly become the Other. Dangerous mysterious and faceless.

The movie rendition of the novel (and it is fiction) is shallow in its representation

of the complexity of the Middle East and should we should effect a re-viewing

of the movie through Edward Said's foundational text Orientalism. If we can allow

for the complexity of the Jewish question and it is without a doubt complex -

I think we can effect an understanding of the issue of Israel form the position

of equals. The movie may have also done a disservice to the Jewish issue through

oversimplification.

Paul Newman is perfect for the hero role of Ari Ben

Canaan - blond and blue eyed with the steely determination of a country looking

for liberation from an almost entire history of victimization. Otto Preminger

should be given credit for great editing and scope. However, the movie does fall

short on the complexity angle and should be viewed with critical eyes.

Literature

What about literature? Using Conradís Heart of Darkness,

we see precisely what Said is referring to when he speaks of the creation of the

Other. If you juxtapose that beside Spivakís read of the subaltern, then you really

have a point of discussion that is both mainstream post-colonial and very helpful

in the examination of Said as a reluctant proponent of post-colonial readings

of text. Spivak's essay "Can the Subaltern Speak?"-- Originally published in Cary

Nelson and Lawrence Grossberg's Marxism and the Interpretation of Culture (1988)--perhaps

best demonstrates her concern for the processes whereby postcolonial studies ironically

re-inscribe, co-opt, and rehearse neo-colonial imperatives of political domination,

economic exploitation, and cultural erasure. In other words, is the post-colonial

critic unknowingly complicit in the task of imperialism?

Is "post-colonialism"

a specifically first-world, male, privileged, academic, institutionalized discourse

that classifies and surveys the East in the same measure as the actual modes of

colonial dominance it seeks to dismantle? According to Spivak, postcolonial studies

must encourage that "postcolonial intellectuals learn that their privilege is

their loss" (Ashcroft. et al 28).

In "Can the Subaltern Speak?", Spivak

encourages but also criticizes the efforts of the subaltern studies group, a project

led by Ranajit Guha that has reappropriated Gramsci's term "subaltern" (the economically

dispossessed) in order to locate and re-establish a "voice" or collective locus

of agency in postcolonial India. Although Spivak acknowledges the "epistemic violence"

done upon Indian subalterns, she suggests that any attempt from the outside to

ameliorate their condition by granting them collective speech invariably will

encounter the following problems: 1) a logocentric assumption of cultural solidarity

among a heterogeneous people, and 2) a dependence upon western intellectuals to

"speak for" the subaltern condition rather than allowing them to speak for themselves.

As Spivak argues, by speaking out and reclaiming a collective cultural identity,

subalterns will in fact re-inscribe their subordinate position in society. The

academic assumption of a subaltern collectivity becomes akin to an ethnocentric

extension of Western logos--a totalizing, essentialist "mythology" as Derrida

might describe it--that doesn't account for the heterogeneity of the colonized

body politic. Philosophy

Philosophically, there is Saidís polemic of his anti-Foucault stance and

his misappropriation of "Discourse". Foucault's focus is upon questions of how

some discourses have shaped and created meaning systems that have gained the status

and currency of 'truth', and dominate how we define and organize both ourselves

and our social world, whilst other alternative discourses are marginalized and

subjugated, yet potentially 'offer' sites where hegemonic practices can be contested,

challenged and 'resisted'. He has looked specifically at the social construction

of madness, punishment and sexuality. In Foucault's view, there is no fixed and

definitive structuring of either social (or personal) identity or practices, as

there is in a socially determined view in which the subject is completely socialized.

Rather, both the formations of identities and practices are related to, or are

a function of, historically specific discourses. An understanding of how these

and other discursive constructions are formed may open the way for change and

contestation. Said posits that this is no point of engagement. The in order for

there to be a point of engagement, the engagement has to come from the top down

rather than the Foucaultian perspective of the examination of Power Relations

which is based on a grassroots appropriation and mis-appropriation of an utterance.

Political Science

Said's work is complex, intertextual and

far-reaching. Barsamian's interviews in The Pen and the Sword are an enlightening

yet they are an incomplete portal to the work and impact of Edward Said. Don't

get me wrong, the conversations with David Barsamian squarely place Said as a

player in an often-oversimplified discussion of a very complex issue - Palestine.

One of the more controversial, yet not often discussed topics is the role

of the PLO in general and Arafat's in particular to the future of Palestine. The

role of Arafat is not to be underestimated - he has single-handedly represented

(or at least single-handedly represented himself as the voice of a nation) the

interests of the Palestinian Arab. What are we to do with Arafat? More importantly,

what at the disparate Palestinian Arabs going to do about Arafat? That is one

of the key questions Barsamian and Said takes up here. If an organization that

was built on "Liberation" is involved in Administration - is it a good thing?

Are the players in this case qualified to perform Administration? If not, should

others be considered to carry the banner? Ironically, you can draw a metaphor

here that is patently Jewish. Moses did the liberation but Joshua took the Jews

to the "promised land" - mind you, I am not making any comparisons of Arafat to

Moses or the notion of the "promised land" as 100% legitimate - I am merely agreeing

with Said that a second look might be advantageous.

One of the major

points is the notion that there will never be normalization of relations unless

the relationship is a relationship of equals:

"We are now on a new stage.

What the Israelis want is a normalization of relationships between Israel and

the Arab states including the Palestinians. Of course I'm all for normalization.

But I think real normalization can only come between equals. You have to be able

to discriminate between tutelage and dependency on the one hand and independence

and standing up as a co-equal with your interlocutor. We haven't done that. That's

why I think it's the most important political task for the coming decade." p.

167.

Edward W. Said's Works

Joseph Conrad and the Fiction of Autobiography.

Beginnings: Intention

and Method. New York: Basic Books.

Orientalism. New York: Pantheon: 1977.

[overview]

The World, The Text, and the Critic

Representations of the

Intellectual.

The Politics of Dispossession.

Culture and Imperialism.

How much simpler can it be?

Said

contra Foucault Said

contra Foucault Kindly

click here to return to Academic Interests

Please

click here to return to Additional Information |