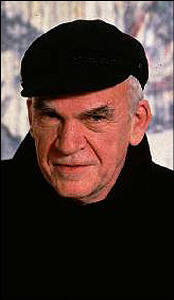

Who

is Milan Kundera?

©2001 by Miguel B. Llora, MA

Kundera, Milan:

Born

April 1, 1929 in Brno, Moravia to Ludvik Kundera, a concert pianist, the younger

Kundera was a jazz musician in his youth. He was a communist party member twice,

from 1948-1950 and 1956-70. He was expelled from the party both times for heterodox

opinions. These political forces affected his employment at the Film Faculty at

the Academy of Music and Dramatic Arts in Prague, where he taught until 1969,

when he was fired and his works proscribed from legal publication in Czechoslovakia.

In response to these restrictions, Kundera emigrated to France in 1975, where

he taught at the University of Rennes from 1975-1978. He now lives in Paris with

his wife, Vera Hrabankova. | Fiction:

Zert (The Joke), 1965; Laughable Loves, 1968; Life Is Elsewhere, 1969; The Farewell

Party, 1975; The Book of Laughter and Forgetting, 1978; The Unbearable Lightness

of Being, 1984; Immortality, 1990; La Lenteur (Slowness) 1994; Identity, 1996;

Ignorance : A Novel, 2002

Essays: The Art of the Novel, 1961; Testaments

Betrayed, 1995.

Movies: The Unbearable

Lightness of Being - Criterion Collection (1988) |

| |

|

| Zert

(The Joke): From the moment I picked up the book, all I could think about

was Kafka - The Castle, Joseph K in The Trial.... Kundera could not seem to escape

his Masters - Kafka, etc. The novel is as intricate as any of his works and somehow

sets the stage for future pieces. By far the most political of his novels, it

is not a political novel. It is a story of human existence. Kundera picks apart

a particular theme, on one level Kundera can be said to be exploring a sense of

the absurd. The four part novel is cleverly written in the first-person narrative.

The novel centers around Ludvik and Helena and the colorful storied surrounding

them and their cohorts. Kundera sets up his heros as antiheros through a series

of humanizing qualities - usually self-centered. Accused of portraying his characters

from a male fantasy perspective, people lose sight of the intricate stories that

he weaves - part advocacy, part parody. Centered around the narrative of the joke

- Ludvik, who being a dedicated communist, finds himself the victim of a joke

he outlined in an open postcard to a young lady he was trying to impress. Locked

in this Kafkaesque drama, his life is one tragedy after another. He becomes a

skeptic. He blames history. We are thrust into a tailspin of the "absurd situation"

we find ourself in. Surface as this analysis has been, kindly look to the deeply

insightful comment that Kundera makes on the human condition through the use of

his characters. I am certain we will all find a little of ourselves in every character.

|  | Laughable

Loves, 1968: I can see why Kundera is the focus of so much controversy and

at times his more profound issues are not given their due. In "Laughable Loves"

as in several of Kundera's other novels, for many of the young male characters,

love comes primarily in the form of sexual conquest, and promises of adventure,

a rare chance to experience the uncommon and feel some sense of empowerment. Granted

that there is this element, the experience of youthful exuberance, it is this

and much more. It seems as though the comical characters who push the hardest

for love are the most disappointed and indeed laughable - so, is it advocacy or

parody? This a chance to poke fun at ourselves. A series of short stories, Kundera

plays in the field of make believe and possibility, and shows us another side

of the human condition. |  | Life

Is Elsewhere, 1969: Exiles inhabit an ethereal place that allows writers to

transcend the everyday and come out with works that both entertain and teach.

Thomas Mann did this for us and Kundera does it in Life is Elsewhere. The action

of the novel centers around the short life of Jaromil, who is a creation of his

mother as a new Apollo to somewhat make up for her loveless marriage. Jaromil

is born in late 1920's, he grows up as a spoiled and sensitive teenager. He engages

in writing lyrical verse, which is heavy into sexual fantasy. As 1948 communist

revolution approaches, he moves on to semi-realistic poetry. At 18 we find Jaromil

as a raging zealot. Jaromil is knee deep in the contradictory actions of reporting

on lapses of professors and to find a girl to ease his physical need to get rid

of his virginity. In this confusion, Jaromil finds himself a mature Stalinist.

As if Kundera where apologizing for his own disappointment (as most intellectuals

of that time where) over the Stalin excesses. The greatness of this book is his

deep insight on adolescent struggle, the longing for maturity and the return to

a lyrical time. Furthermore, he takes us through the experience of longing for

the fame in the lone wolf and the need to return to the herd. Here Kundera fuses

(which is once again the mark of his greatness) the deeply interwoven existential

questioning with the ribald sense of humor that he masks the questioning around.

The book is not really about Jaromil at all, it is about what he mentions early

on in the novel, it is the attitude of the 'lyrical attitude' . "The lyric age

is youth. My novel is an epos of youth, and an analysis of what I call "the lyrical

attitude." The lyrical attitude is a potential stance of every human being; it

is one of the basic categories of human existence. Upon reading that, I felt that

I was reading Nietzsche and Heidegger all over again. That man is not static but

becoming. Besides, Kundera does quote Heidegger: "The novel, of course, does not

answer questions. The questions are already an answer in themselves, for Heidegger

put it: the essence of man has the form of a question." Kundera presents to us

the ridiculous nature - he does this in The Unbearable Lightness of Being - that

life is not a thing we can repeat - it is this life and no other. Maybe if we

can laugh at Jaromil, we will find the strength to laugh at ourselves as if we

all don't have a little Xavier inside us. |

| The

Farewell Party, 1975: Set against the backdrop of a Central European spa town,

Kundera once again orchestrates his polyphonic style to intertwine lives and stories

to play out a small portion of the human condition. In what seems like an orgy

of loves unfulfilled, partnership of the most unlikely kind; a nurse, her boyfriend,

an American, a famous musician and his wife and a potential émigré and his ward

mix and mingle and form some sort of relationship soup that manages to hold together.

Despite the playful tone of the story and dialogue, "Farewell Waltz" deals with

the profound issue of the fragility of life. Far be it for Kundera be labeled

a symbolist, the blue pill speaks to me of how easy it is to choose the back door

of living and to cash it all in for one reason or another. On one level, the accidental

taking of the pill by Ruzena shows us just how easily life can be taken away.

With Kundera's books you can be guaranteed that is that and much more. The irony

of Dr. Skreta lies in his bizarre power to create - a very Mary Shelley touch

- of science without soul. Makes me stop to think about the true nature of my

origin. Over and above all this, Kundera play on how human we are and celebrates

the fragility, the emotion and the universal need for love.... |

| The

Book of Laughter and Forgetting, 1978: A complex piece of public vs. private,

the book is really less about laughter and more about forgetting. Tamina submits

to Hugo, hoping that in turn he will find a way to bring back her cherished diary

- her only mode of remembering. We see a different set of Kunderan issues in this

book, where like Tomas in the Unbearable Lightness of Being, the characters find

in their private erotic lives, the empowerment and freedom they so lack in the

public arena. In a sea of disappointment, all the characters seem to fail to achieve

their goals what is clear from Tamina's experience is that all this possibility

in the erotic sphere comes with as much risk as it does promise. As is evidenced

by the suffering of Tamina, few of his characters go unscathed. Just like the

story of the hat, it is clear that remembering is a sort of forgetting. In a world

of broken dreams, we tend to find places of solace and comfort despite the risk.

We laugh, we cry, we forget, we remember, we live the tension and live out our

Nietzschean potential, picking and choosing what we remember. A celebration of

our human, all too human, side. Another Kundera triumph. |

| The

Unbearable Lightness of Being, 1984: In the novel The Unbearable Lightness

of Being, Milan Kundera takes great pains to mask what is essentially, an indictment

against lightness. Through a process of purposeful ambiguity, Kundera sets up

three important and interrelated themes in the novel. These three themes need

to be examined at some length in order to understand Kundera's complexity and

unravel his indictment against lightness. Firstly, there is the psychological

construct of the eternal return as developed by Friedrich Nietzsche. Kundera begins

The Unbearable Lightness of Being with: The idea of eternal return is a mysterious

one, and Nietzsche has often perplexed other philosophers with it: to think that

everything recurs as we once experienced it, and that the recurrence itself recurs

ad infinitum! What does the mad myth signify? Putting it negatively, the myth

of eternal return states that a life which disappears once and for all, which

does not return, is like a shadow, without weight, dead in advance, and whether

it was horrible, beautiful or sublime, its horror, sublimity, and beauty mean

nothing.(1) The eternal return forms the foundation of the discourse of the opposition

between lightness and weight. The eternal return moves us to reconsider whether

the accidental nature of human existence (einmal ist keinmal) makes it less significant.

Is lightness positive or negative? Parmenides posits that lightness is positive.

Kundera's position is that it is negative. Kundera and Nietzsche see the heaviest

of burdens as the image of life's most intense fulfillment. Nietzsche and Kundera

advocate the need for significance, which springs from weight as if both were

synonymous. Kundera asks us what the mad myth of the eternal return signifies

in all of its perplexity. The perplexity is played out in Kundera's stories within

stories. Secondly, through the love story of Tomas, Tereza and Sabina, Kundera

plays out his indictment against lightness. Within this braid of interwoven relations,

Kundera places the duality of lightness and weight side by side, seemingly not

endorsing one or the other. To give a better picture of the dynamics that surround

the three main characters it is important to focus on each character separately

and then in relation to each other. Kundera creates complex characters with hard

choices and unique circumstances. Despite the purposeful ambiguity, the search

for meaning leans towards the necessity of significance, which comes from a sense

of weight. Thirdly, Kundera plays out his indictment against lightness in the

public arena, placing the personal stories within the historical framework of

the Russian invasion of Czechoslovakia in August of 1968; through this mechanism

history becomes another story within a story. Are events forgiven in advance because

they happen only once? Kundera poses questions of historical significance surrounding

the Russian invasion of Czechoslovakia. History repeats itself while collectively

we tend to forget that a similar event occurred previously. We regard events with

little significance because we see occurrences in isolation, never to happen again.

In this sense, his indictment against lightness is justified, accurate and timely.

The Czech experience reflects the duality of lightness and weight within the context

of the eternal return. How? Collectively, do we negate or affirm the takeover? |

| Immortality,

1990: Who of us does not, at least for moment, wonder what people will think

about us when we are gone. What kind of a legacy we leave behind seems to be important

to some people.... apparently it is to Kundera. For in his mind, Goethe seemed

fixated by it. Whether is "big" immortality or "little" immortality the end is

the same. Agnes, Laura, paul, Bernard, Goethe, Rolland, Eluard and Rilke. Beethoven

and Bettina.... Bettina. Kundera takes us from the everyday to the historical.

Did this all really happen.... Who really cares? The twist and turns as well as

the one thing that Kundera does best - to take on one particular aspect of the

human condition - in this case Immortality. One of his most complex novels, it

follows "The Unbearable Lightness of Being" in its lyrical style and the voices

and narratives. There are few writers like Kundera who can take us from the one

scene to the next and yet it seems to flow, like it is common and should be happening.

Is there a Nobel Prize waiting in the wings? There should be. Next to "The Unbearable

Lightness of Being", "Immortality" is head and shoulders above the rest in terms

of complexity and breadth. |  | La

Lenteur (Slowness) 1994: There are those who read Kundera for the deep philosophical

meandering and those who like him for the literary gymnastics. I have to admit

to being a lover of both. I can see the hard core philosopher types locked in

a heavily wooded library trying to suck up every ounce of profundity from The

Joke, Testaments Betrayed and The Art of the Novel, while the rest of use are

in a cafe reading The Unbearable Lightness of Being, The Book of Laughter and

Forgetting, Life is Elsewhere and of course, Immortality. Whichever side you see

yourself, there will be something for you in Slowness. You will see the typical

Kundera style of the ever present Kundera voice - and obtrusive author. For the

philosophical in us, we will read about a narrator and his wife, who are taking

an unplanned holiday, driving down a country highway in search of a romantic chateau.

Impatient, the narrator inquires: "Why has the pleasure of slowness disappeared?

Ah, where have they gone, the amblers of yesteryear? Where have they gone, those

loafing heroes of folksongs, those vagabonds who roam from one mill to another

and bed down under the stars?" This becomes the philosophical foundation for the

magical literary gymnastics that is Kundera's playground. Kundera spins many tales.

Tales as laughable as they are profound. We are transported to an AIDS charity

feast, famine ravaged Somalia, Henry Kissinger's White House Office. For the archivist

in us, Kundera does not let us down. He comes back to the theme style he used

in previous novels, this time, it is "staying fixed". As is common with Kundera,

he spins his purposeful confusion and takes on a roller coaster ride of literary

magic that I don't mind taking. In the end, I walk away with, the rate with which

we do things is directly proportional to the rate with which we forget things.

By far not his most profound novel, the residue of greatness still lingers - it

is too bad that to date, a Nobel Price has eluded him - for the range and greatness

of his work, Kundera should be richly rewarded, but then again, they missed Borges

as well - so what else is new, eh? In about 156 pages I have once again been transported

to the Bohemian countryside that in my lyrical youth I learned love so much. In

a new western world obsessed with Ayn Rand - stop to meander, laugh and be entertained,

in a world of Slowness. |  | Identity,

1996: Kundera plays with the fractured self in this book. I agree that the

core of the book centers around the unknowable "other". Often times we think we

know someone and we find we are surprised. Kundera loves to play in the field

of human relations and this book is not exception. If you take the book for itself,

then you will see a richly textures interplay between two people Chantal and Jean-Marc

and the personal "issues" that plague them. If you place this in the context of

the richly ornamented and finely crafted works that are The Unbearable Lightness

of Being, Immortality, The Book of Laughter and Forgetting - the book looks less

like a unique work and more like Laughable Loves. The difference between this

and The Hitchhiking Game is that the HHG plays around in the area of role playing

while Chantal seems to be really to "find" rather than "create" herself. I guess

we are all in some sense "creating ourselves". Kundera does like to work around

in the dangerous area of fidelity and makes it all a matter of choice. I am confused

about the statement made by the reader from Chicago who wrote on march 30, 2001

"He attempts, instead to achieve what Kafka did: the creation of an alternate

reality". As much as I love Kafka, I have a hard time placing them on the same

page. Anyway, good observation. I would place Kafka in the realm of Borges and

as an inspiration for Kundera - but the two are mutually exclusive. All this said,

on its own it is a good book but does not deserve a place beside his classics. |

| The

Art of the Novel, 1961: Foucault posits that the authorial function is a discourse

all its own. As if to say that authors, publishers, readers, marketers, etc.,

are part of an elaborate mechanism that gets between the reader and the text.

Milan Kundera is a master of his authorial function and does not disappoint with

"The Art of the Novel". In this work, Kundera goes beyond "Testaments Betrayed"

(a work that examines the efforts of Max Brod on behalf of Kafka and Janacek)

and addresses issues surrounding Kundera's own work. Given the forum to further

discuss topics like kitsch; and no make mistake, Kundera understands his authorial

function. The book contains discussions of Cervantes, Kafka, Broch, Musil, Dostoevsky,

Tolstoy, Sterne, Falubert and Balzac, as if revealing his entire array of inspirational

sources. Furthermore, the compact but dense book also deals with the Czech Republic,

totalitarianism, Stalinism, Kitsch, Central European Culture, modernity, the novel.

I often wonder what prompted this almost apologetic work. Conversely, the range

and complexity of Kundera's ouevre is astounding as it is controversial. Loaded

with sexuality, I often wonder if his commercial success is the reason the Nobel

people have overlooked his profound inquiries. As the novel is the playground

of possibility, can an explanation of one's own work enhance it - sure it does.

A must read for Kundera scholars. |

| Testaments

Betrayed, 1995: Readers will no doubt be reminded of Art of the Novel, a more

careful reading will reveal that the major theme of the book, the posthumous betrayal

of artists and their work, was also dealt with to a large extent in Immortality.

In Immortality, Kundera allowed for the posthumous encounter of Hemingway and

Goethe. Where Goethe speaks candidly to Hemingway and mentions that "Haven't you

realized, Ernest that the figures they talk about have nothing to do with us."

Dealing mostly with Max Brod's betrayal of Kafka, Kundera is simply standing up

for the rights of artists wishing that artists wishes and rights be honored. Kundera

brings in his vast knowledge of music to the discourse of the novel stating in

effect that each section carries a tempo which indicates a change in atmosphere.

Effectively, Testaments Betrayed is a 9 part piece that covers a range of subjects

from the history, the life, and the death of the novel, Hemingway, Kafka, Janacek,

Stravinsky and Don Quixote. Not to reduce Testaments Betrayed to a single theme,

the focus does seem to be the betrayal of Kafka by Brod. Kundera describes how

Kafka suspends believability not to escape the world but to capture it. When Max

Brod refuses to burn Kafka's papers, he effectively creates Kafkology. Kundera

notices the parallel fate of Kafka and yet another of his heroes, Leos Janacek

causing his provincialism and isolating him from mainstream music. Effectively,

"a dead person is treated either as trash or as a symbol. Either way, it's the

same disrespect to his vanished individuality." I line with what Foucualt and

Barthe are talking about when talking about the 'Author Function'. I guess it

is really ironic that betrayal comes from the best intentioned. Kundera no doubt

is controversial where this is concerned as I can imagine the career Kafkologist

will disagree with him and see Brod as a hero - the one who saved Kafka from obscurity.

No matter what your opinion, Kundera is just as responsible for all the authorial

function violations by brining it all up - more power to him. |

| Ignorance

: A Novel, 2002: Kundera cleverly joins the story of Odysseus with his own

musings of coming home and the dread that such a scenario provides. Once again,

we see Kundera distract us with unrealistic love affairs while he diverts our

attention from the musings related to fate, history and nostalgia. Ignorance,

unfortunately seems hurried and in the end doubtless this book will produce in

his most ardent supporters a nostalgia for Kundera at his most profound. Although

the "intrusive author" technique for which Kundera is famous for is

all over this book, it seems to lack the density of such books as The Unbearable

Lightness of Being and Immortality. Josef and Irena return to Prague after an

extended absence. Josef returns to form some closure in relation to his deceased

wife. Conversely, Irena is convinced by a friend that it would be exciting to

return to Prague after all these years. Both find much like Odysseus that they

are returning to a very different "home." Both sink into each others

arms in a hurried episode of lovemaking that somewhat reflects the disappointment

of the journey home. Kundera's last three books: Identity, Slowness, and Ignorance

do not have the same complexity as the major works like The Unbearable Lightness

of Being, The Book of Laughter and Forgetting, and Immortality. It is as if the

writer is tired and simply revisiting his old themes - remembering, history, and

unrealistic affairs - affairs that are only possible in the imaginary space of

fiction. Although it is the hallmark of Kundera's genius to blend the historical

(Oedipus, etc. - in this case Odysseus) there does not seem to be anything REALLY

original in this work. As mentioned earlier, it leaves me nostalgic for Kundera

at his most profound and most playful. |

| The

Unbearable Lightness of Being - Criterion Collection (1988): Kaufman turned

a complex book into a simple love story. If one wishes to review the movie for

itself sans the book, you see a love story based on personal preferences and bad

Czech accents. However, if you review the the movie within the context of the

book, it falls flat in many places. No one can argue the beauty and exoticism

and beauty of Prague shines through and Kaufman's treatment of the Czech invasion

superb. What the movie seems to fall short on is the nature of Tomas's existential

angst - the tension between lightness and weight. Tomas is played up against the

backdrop of the Oedipus story and not against Nietzsche's eternal return. Alright,

you have to consider that two hours to play out what needs a whole book to explore

is not easy. I am really disappointed in the movie after having spent so much

time with the book. The characterization of Tomas, Sabina and Tereza by Daniel

Day-Lewis, Lena Olina and Juliet Binoche allows it a soft landing. Where was Franz

in the whole scheme of things? In the book, Franz is a really integral part of

the consideration of the lightness contra weight consideration although his role

is really to play up Kundera's "Life is Elsewhere" theme. In the movie Franz is

bit part. Lacking the full complexity of the book but beautiful in its location

and eroticism,the movie manages to work. Although, it is bad enough that Kundera's

work is sometimes reduced to male fantasy, do we have to confirm it via a movie?

| | | |

| | |

| Understanding

Milan Kundera: Public Events, Private Affairs (Understanding Modern European and

Latin American Literature) by Fred Misurella: Fred Misurella takes Milan Kundera

and makes him accessible.

Not that Milan Kundera is incomprehensible, it

is just that there are so many twists and turns sometimes a little help is all

we need. Misurella is good at noting the parabatic asides and is excellent at

zeroing in on some of the key themes that Kundera explores. His read on "The

Joke" is so comprehensive, it is almost a must to have this book with you

like dictionary.

His reading of "The Unbearable Lightness of Being"

is really interesting. Taking the approach form a Oedipus angle, Misurella misses

some of the subtle Nietzsche and Tolstoy angles that Kundera includes. "The

Unbearable Lightness of Being" is full of references to "The Eternal

Return" and "Anna Karenina" that it is impossible to miss - and

Misurella misses this by placing the Oedipus read at the center.

If you read

"Understanding Milan Kundera" along side Maria Nemcova Banerjee's "Terminal

Paradoxes" and John O'Brian's "Milan Kundera & feminism : dangerous

intersections" then you will get a greater appreciation for the complexity

of Kundera's work.

If you use the book as a reader, then you will have taken

advantage of the book already. However, Misurella does an ending with "The

Art of the Novel" that brings Kundera's work together very nicely. It is

impossible to even try to do a comprehensive piece of Kundera as the body of work

is so huge and complex. Misurella does a wonderful job of taking such a complex

subject and making is accessible for folks like me. I recommend it highly along

with the other books above. I'm sure Kundera would agree. |

| Terminal

paradox: The novels of Milan Kundera by Maria Nemcová Banerjee: Arguably

one of the greatest contemporary writers around, Milan Kundera is one of the most

difficult writers to read and analyze. I say this because he can be read on many

levels. To get a much richer and fuller read, there is no escaping the work of

Maria Nemcova Banerjee. In "Terminal Paradox: The Novels of Milan Kundera"

Banerjee cuts through the complex intertextual basis for Kundera's work. Kundera

is heavily influenced by the likes of Cervantes, Nietzsche, Kafka, Rabelais, and

Tolstoy - to name a few. To be able to "really" understand Kundera with

some depth and understanding you need to have an understanding of his masters

- Banerjee does this for us - she creates a roadmap. I am not saying that you

can stop now and consider her work a substitute for gaining access to this deeper

understanding of Kundera's work - but it sure makes it much easier. If you wish

to undertake a serious academic consideration of Kundera's work - "Terminal

Paradox - The Novels of Milan Kundera" is an invaluable resource and I recommend

it highly. | Kindly

click here to return to Academic Interests

Please

click here to return to Additional Information |

MILAN

KUNDERA: AN INDICTMENT AGAINST LIGHTNESS

MILAN

KUNDERA: AN INDICTMENT AGAINST LIGHTNESS The

Joke - Reading Circle or Book Club Summary and Questions

The

Joke - Reading Circle or Book Club Summary and Questions