An Introduction to Philip Roth

*information

collected and arranged by Jennifer Fox

for her colleagues at San Diego State

University

©2002 by Jennifer

Fox

Thank you

hosted @ http://www.mllora.com

DEDICATION:

This site is dedicated to my colleagues and reading circle participants at the

Masters of Arts in Liberal Arts and Sciences (MALAS) program at San Diego State

University (SDSU).

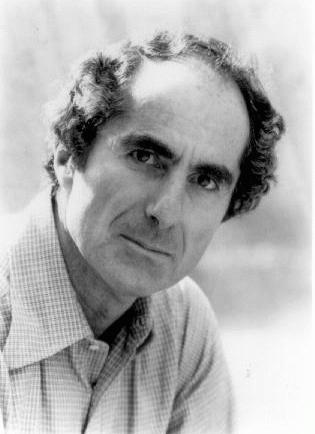

Philip

Roth:

Philip Roth was born in Newark, New Jersey, in 1933 and was educated

at Bucknell University (B.A.), and the University of Chicago, where he completed

his M.A. and taught English. He then taught creative writing at both Iowa and

Princeton. Roth's narrative is inventive and audacious, the characters are sharply

drawn, their neuroses painfully apparent. He received the National Book Award

in 1959 for his debut work, Goodbye, Columbus, and Five Short Stories,

which shocked the synagogue and delighted readers with his provocative exploration

of young man's sexual angst. His candid look at the Jewish American male's psyche

continued in his 1969 novel Portnoy's Complaint, a comic representation

of his middle-class New York Jewish world, and perhaps his best known novel. His

other works include the Nathan Zuckerman novels: My Life As a Man, The Ghost

Writer (1979), Zuckerman Unbound (1981), The Anatomy Lesson

(1983), and The Counterlife (1988), which won the National Book Critics

Circle Award. Among his memoirs are The Facts, Deception, Operation Shylock,

and his 1991 memoir, Patrimony: A True Story, in which Roth writes

a moving account of his father's illness and death.

http://www.lectures.org/roth.htm

The

Counterlife: Summary and reading circle questions by Jennifer Fox ©2002

Roth's Counterlife: Destabilizing The Facts

1

After

Philip Roth had published The Counterlife, his thirteenth novel, in 1986,

the last thing his readers expected next from him was an autobiography aspiring

to tell the facts. Roth's fiction has traced a path from the relatively realistic

to an extremity of self-reflexivity. He described The Counterlife as a

novel which "progressively undermines its own fictional assumptions"

[emphasis mine] (Milbauer and Watson 11), and it has many of the characteristic

features of postmodernist fiction - fictions within a fiction, characters dying

and then being resurrected by their author, characters refusing to participate

in the fiction - it shows, in fact, every indication of succumbing to the metafictional

disease so deplored by many American reviewers. With the appearance of The

Counterlife Roth was accused by critics such as Josh Rubins of joining the

disreputable ranks of John Barth and Gilbert Sorrentino in an attempt to pander

to the depraved tastes of academics.

Imagine the surprise of his postmodernist readers when he followed The Counterlife with The Facts: A Novelist's Autobiography(1988). His aim, he declares in the opening section of the book, is to work backwards, stripping what he had already imagined "so as to restore [his] experience to the original, prefictionalized factuality" (3). If those offended with the presumed pretentiousness of The Counterlife were placated, Derrideans must have begun muttering about Roth's naive appeal to the myth of origin before they reached the second page of the book. The provocations continue. Ignoring Benveniste's assertion that the first-person singular pronoun is the only one that cannot refer to anything because it transcends the structure of oppositions on which the pronoun is based (Problems Ch. v) , Roth asserts: "the person I've intended to make myself visible to here has been myself, primarily" (4). He refers to his excursion into autobiography as a strategy by means of which he "began rendering experience untransformed" (5) Does the writer of The Counterlife seriously consider that memory is infallible? Or is this rather the exasperated outburst of a writer who has for too long been faced with the perverse "misreadings" of his reviewers who have insisted, as he put it to one interviewer, that he is "the only novelist in the history of literature who has never made anything up" (Roth, Reading Myself 135).

Roth refuses to hide behind such an excuse. His stated reason for so uncharacteristic a departure into a genre which supposedly "faithfully conforms to the facts" (7) was a breakdown that Roth suffered in the spring of 1987 caused in part by the side effects from an accidental mixture of painkilling drugs. The depression into which he fell made him distrust the transformatory powers of the imagination on which he had relied to turn his ordinary life into the dazzling pyrotechnics of his fiction. "If this manuscript conveys anything, it's my exhaustion with masks, disguises, distortions, and lies" (6). The dispersion of the subject in a textual maze can apparently produce "real" mental anguish and illness. In The Facts he sets out to "demythologize" himself as a form of therapy--"demythologizing to induce depathologizing" (97), he writes, immediately reverting to that world of verbal slippage that he is simultaneously re/denouncing. This was all he could do, he claims, "so long as the capacity for self-transformation and, with it, the imagination were at the point of collapse" (7). So! This factually based book is his only defence against the imaginative and textual anarchy that threatened otherwise, he claimed, to reduce him to silence. We already know that the therapy was successful, that his imagination has returned (if it ever left him), that his addiction to self-transformation has taken the fictional form of his next novel, Deception (1989), in which "Roth" features as his own protagonist. But a closer reading of The Facts will show that this recovery takes place earlier than he thinks--in the course of writing the book, not as a consequence of having completed it.

In an interview with Katherine Weber in Publishers Weekly Roth revealed the "fact" - already a problematic term - that he began by writing three or four page fragments about his childhood purely as a form of occupational therapy with no intention of writing an autobiography. Those early sketches evolved into the first of the five sections into which the main portion of the autobiography is divided. When he was at about midpoint in the book he wrote the letter to Zuckerman, his fictional alter-ego in the trilogy, Zuckerman Bound, and in The Counterlife, with which The Facts opens. "I began writing about why I was writing the book," he explained ("Philip Roth" 68). This concern quickly supercedes his earlier concern for getting at the facts. At one point he even considered having Zuckerman comment in the margins of the manuscript. Instead he opted to bracket the autobiographical content with his letter to his fictional counterpart at the beginning and Zuckerman's reply at the end.

The supposedly factual main portion of the book, then, is framed by a fictional correspondence between the narrator of his fiction and his principal fictional protagonist for the last decade. "In some ways," he explained to Katherine Weber, "you could say this is a sequel to The Counterlife" - a sequel, that is, to an earlier work of fiction. He added, "with the Zuckerman and Maria letters, I was working my way back into writing fiction" ("Philip Roth" 68, 69). Both works, novel and autobiography, end with fictional personae asking to be let out of the verbal construct that has given them whatever form of life they enjoy--or rather don't enjoy. What has happened to the distinction all too crudely drawn in Roth's opening letter to Zuckerman between "conform[ing] to the facts" (7) and "making fictional self-legends" (8)? Clearly the author has achieved more than simply the recovery of his imaginative powers in the course of writing the book. He has also collapsed autobiography into fiction; that is, he has traced his growing recognition of the indeterminacy of all forms of textuality. Setting out to write a kind of res gestae, he has ended with the implicit recognition that, as Marc Eli Blanchard writes, "autobiography reflects only itself" ("The Critique of Autobiography").

It is significant that Roth has reordered the sequence in which he says he originally composed the material of this book - a sequence that reflected his gradual recovery from an over-active imagination. The opening sections of the autobiographical memoir may represent a therapeutic flight from the tyranny of his imagination. As Roth explained to Jonathan Brent in the New York Times Book Review, "a menaced self can't successfully entertain any more illusion than what's already hounding it into despair" ("What Facts?" 46). But the published book opens, not with these sections, but with Roth's letter to the fictional creation of his imagination asking him whether he should publish the manuscript or not. At the end of the book Zuckerman answers his question in no uncertain terms: "Don't publish--you are far better off writing about me than 'accurately' reporting your own life" (161). So not only does Roth open his autobiographical narrative by submitting it to the judgment of the imagination, but he ends by acknowledging the superiority of an imaginative over a factual form of narration. Fiction, he discovers, is more believable (and readable), though not necesarily truer, than fact.

Following the opening letter is a brief Prologue also written later than the first section that evolved out of those brief fragments. While the first of the five main chronologically ordered sections opens with Roth already halfway through his childhood, the Prologue adopts a synchronic strategy by invoking the timeless images of his already dead mother and his dying father. He superimposes the image of his father nearly dying from peritonitis when Roth was eleven with a moving picture of his father at the time he was writing The Facts facing the imminence of death. "Trying to die isn't like trying to commit suicide--it may actually be harder, because what you are trying to do is what you least want to happen; you dread it but there it is and it must be done, and by no one but you" (17). What gives this sentence its power is not the fact that his father was indeed dying (he died late in 1989; Roth published a memoir of his father, Patrimony, in 1991), but Roth's use of his imagination to see death from his elderly father's point of view - or rather from how he believes he would feel if he were in his father's shoes. Facts of this kind can only be rendered satisfactorily through the artist's imaginative prism.

Similarly in the Prologue his mother is imaginatively metamorphosed into "a sleek black sealskin coat into which I, the younger, the privileged, the pampered papoose, blissfully wormed myself whenever my father chauffered us home..." (18). By resorting to a partly poetic use of language, Roth textually transforms his younger self into a young American Indian child carried in its mother's fur coverings. The fifty five year old writer can be seen here remaking his image from that of a Jewish outsider with immigrant forebears to that of an indigenous American. The Prologue, then, has little to do with the facts, although it never flouts or questions them. It functions as a dream image or fantasy of the world as Roth fashions it, a verbal construct that answers his personal needs at the time of writing. These needs include, as he tells Zuckerman, the need to return to a moment of life when "one's own departure is unconceivable because they [his parents] are there like a blockade" (9). This rearrangement of the original order in which he composed the book shows how Roth's earlier concern with self-therapy is supplanted in the course of writing by a concern for literary form. As he pointed out to one interviewer: "Writing leads to controlled investigation. The object of analysis is uncontrolled investigation" ("Philip Roth" 69). However it is open to question to what extent literary form is controlled and to what extent it is produced by the uncontrollable unconscious to which analysis attempts to give expression.

Literary form embodies the shape of the writer's dominant obsessions. Roth has described the book as "a portrait of the artist as a young American" ("What Facts?" 3). Already one can observe Joyce's shadow and the Bildüngsroman merging intertextually to shape Roth's narrative along predetermined generic lines. In his long concluding letter Zuckerman claims to understand the plan of the book: "In somewhat autonomous essays, each about a different area in which you pushed against something, you're remembering those forces in your early life that have given your fiction its character and also reflecting on the relationship between what happens in a life and what happens when you write about it" (164). The five central sections follow Roth's life from about the age of ten to his thirty-sixth year (1969) when Portnoy's Complaint was about to be released on an unsuspecting world. By the fifth section, in which Roth diagnoses all the different elements (factual and literary) that went into the make-up of the fictional Portnoy, the relationship between fact and fiction has become extraordinarily complex if not disentanglable. This is the whole point of the book, to show how ultimately you cannot separate the facts from the imaginative transformation they undergo as soon as they become part of a textual web, whether that web passes as fiction or autobiography. The therapy takes the form of recognizing that the imagination, however tyrannical, plays an inescapable part in any textual reconstruction of the memory.

The first section is titled "Safe at Home." It concentrates on Roth's teenage years in the Jewish Weequahic neighbourhood of Newark, New Jersey. The whole section smacks of his original intention of getting back to the facts. But how much credence do these facts have on the traditionally suspicious reader of autobiography, especially when it is written by Roth? His childhood turns out to have been unusually safe. Apparently he enjoyed a virtually untroubled relationship with both parents whom he admired and loved. Only once in passing does he let drop a hint of experiencing the usual strain that develops between parents and their children in their later teens. Among the subjects of conversation that he and his friends would talk about as they wandered the streets was that of "being misunderstood by our families..." (31). The only signs of a hostile world outside his Jewish enclave were occasional raids by gentile boys from rival schools. And these were the exception: "our lower-class neighbourhood...was as safe and peaceful a haven for me as his rural community would have been for an Indiana farm boy" (30). Once again here one catches Roth projecting his fantasies of a quintessential American boyhood onto his ethnically segregated childhood.

Overall the entire opening section is bland, anodyne, and pretty unbelievable. The whole tenor of this section may be an unconscious riposte to those readers of Roth's fiction who have insisted on reading Portnoy's lurid adolescent struggles with his parents as a thinly disguised account of his own childhood. But at the conscious level Roth was clearly aware of his reader's likely incredulity by the time he came to write the long concluding letter from Zuckerman, the spokesman for Roth the novelist. There Zuckerman alleges that "what's on the page is like a code for something missing" (162). Is this composite, Rotherman, merely focusing on Roth's reticence as a way of disarming the inevitable objections to his overly sweet account of his boyhood? Or is he simultaneously making a sophisticated comment about the complex nature of the autobiographical act that he has discovered in the course of writing about his life? Is he being defensive, or metanarrational, or both? Because it is a truism that a characteristic of the genre is that it implicitly provokes the reader into an act of hermeneutic interpretation, challenging one to penetrate the surface text, and make inferences about the autobiographical narrator/protagonist from gaps and absences in that text. Maria represents this typical reaction when, after reading the manuscript of the book, she says, "I'm interested in the things an autobiographer like him doesn't put into his autobiography" (190).

Zuckerman points out that Roth's reticence is not confined to the content. The Facts is also characterized by his "refusal to explode" (162), to indulge that carnivalesque love of obscenity and emotional excess that accounts for much of the success of Roth's fiction. Because that excess involves a use of exagerration and caricature to be found in the novels of a Dickens or a Fielding, it is normally eschewed by writers of autobiography anxious to maintain the illusion of mimetic accuracy. Through Zuckerman Roth draws his reader's attention to the way his vain attempt to stick to the facts ends up excluding vital facts (such as his need for that anger simmering just beneath the surface) that explain why he writes the kind of books he does. Yet even before Zuckerman's letter, in the fifth section he is openly talking about his discovery in his twenties of this "destructive force" (145) that erupted in "reckless narrative disclosure" (137). Clearly the autobiographical narrative has undergone a sea change in the course of its writing. The first section ends with Roth in 1982 meeting the mother of a childhood friend who exclaims nostalgically: "Phil, the feeling there was among you boys--I've never seen anything like it again.'" He adds, "I told her, altogether truthfully, that I haven't either" (34). That sugary conclusion to the section with its provocative appeal to "truth" immediately arouses the reader's suspicions about the nature of autobiographical memory. The text here and elsewhere draws attention to itself as an opaque object and away from the facts it is re-presenting as a supposedly transparent medium.

The second section, "Joe College," covers Roth's years in the early fifties at Bucknell University, in Lewisburg, Pennsylvania. It is divided into accounts of his choice of a Jewish in preference to a non-denominational fraternity, his editing of an alternative literary magazine, his participation in an élite two-semester seminar, and his first affair with "Polly." Once again Zuckerman identifies the average reader's source of unease at this account of Roth's tranquillized years at university. There is a disparity between Roth's depiction of his school and student days as "an idyll, a pastoral. allowing little if no room for inner turmoil..." (169), and the personal hell on earth that follows when he becomes involved with "Josie," the woman who fakes a pregnancy in order to trick him into marriage and who after they separate faces him with the prospect of paying alimony for the rest of his life. Sections one and two offer no preparation for, or explanation of, the personal horror that he experienced in the period covered by section three, as Zuckerman is quick to demonstrate:

As you yourself point out, Josie isn't something that merely happened to you, she's something that you made happen. But if that is so, I want to know what it is that led to her from that easy, wonderful, shockless childhood that you describe, what it is that led to her from the cozily combative afternoons with Pete and Dick at Miss Martin's seminar (169).

Zuckerman's is applying a fictional criteria to find this particular aspect of the supposedly factual narrative wanting. But it is also possible that the intense unhappiness of the years with "Josie" have falsified by comparison Roth's memories of his earlier years, inducing him to see them through rose-colored spectacles. What he takes to be the facts of his early life have been powerfully bleached in the developing process in order not to render the period with "Josie" in melodramatic blacks. Emotional and aesthetic forces unite here to distort the irrecoverable facts.

Is Roth first dramatizing (in the opening two sections) and then commenting on (in the concluding letter) the way that character is a textual construct that requires the maximum licence offered by fiction to acquire substance within the textual framework? Are all protagonists of autobiography necessarily handicapped as what narratologists call "actants"? Roth has Zuckerman point out the all too obvious fact that he, Roth, is "the least completely rendered of all [his] protagonists" (162). Wittily Roth has Zuckerman argue for the superiority of his own construction as a fictional character to that of the protagonist of The Facts. "You are not an autobiographer, you're a personificator" (162). Most tellingly he suggests that Roth has become the sum of all the fictional personae that he has produced in the meantime. "By now what you are is a walking text" (162). The first two sections illustrate this poststructuralist position: behind that walking text lurks a chimera, an absence, Roth's Other.

2

In Roth's opening letter to Zuckerman he makes the astonishing claim that "this

feels like the first thing that I have ever written unconsciously and sounds

to me more like the voice of a twenty-five-year-old than that of the author of

my books about you" (9). If one accepts Lacan's interpretation of Freud (as Zuckerman

appears to do) it is nonsense to persuade oneself that any text reflects the unconscious,

since we all create our unconscious when entering the symbolic order, an order

of language among other things. Language is what forever divides us from our unconscious,

whether that language is used for fictional or autobiographical purposes. It is

only in the lacunae between words that the unconscious might be glimpsed

endlessly deferring meaning along the signifying chain. Is Roth once again setting

the reader up here? Is he trying to draw the reader's attention to the problematical

nature of his claim by the use of two similes in the same sentence ("feels...like"

and "sounds...like")? Zuckerman, his sophisticated alter-ego, is quick to ask,

"Do you mean that The Facts is an unconscious work of fiction?" and ends,

"Is all this manipulation" [including "the very pose of fact-facer"] "truly unconscious

or is it pretending to be unconscious" (164)? The very presence of Zuckerman acts

as the embodiment of the split subject, everything in Roth that he finds he has

to repress in order to conform to the requirements of autobiographical generic

conventions. Zuckerman, the personification of the licence of fiction, taunts

the disadvantaged autobiographer with his inability to exclude his fictional counterpart

either in spirit or in person from a narrative aspiring to be factual.

The third section introduces a new note of irony and ambivalence into the narrative. Coming midway through the book, this section allows the doubts that Zuckerman expresses so explicitly at the end to come closer to the surface. Even the title of the section is ironical - "Girl of My Dreams" - an allusion to "Josie" with her "undiscourageable imagination unashamedly concocting the most diabolical ironies" (111). Although the book becomes more interesting with the harrowing tale of Roth's sad romance with her and their sadder marriage ending in separation after three years, comparison of this account with the enraged voice of Peter Tarnopol in My Life as a Man (1974) exposes the inferiority of the autobiographical version to the earlier fictionalized rendering of the same events. What made Roth undertake this suicidal rewrite when he had admitted to an interviewer back in 1984 that the facts were virtually irretrievable by then?

It [the marriage] took place so long ago that I no longer trust my memory of it. The problem is complicated further by My Life as a Man, which diverges so dramatically in so many places from its origin in my own nasty situation that I'm hardput, some twenty-five years later, to sort out the invention of 1975 from the facts of 1959. (Roth, Reading Myself 149)

It is not simply impossible to disentangle fact from imaginative invention; it is impoverishing. As Zuckerman observes, "The truth is that the facts are much more refactory and unmanageable and inconclusive, and can actually kill the very sort of inquiry that imagination opens up" (166). The interesting question that arises from this and other interventions by Zuckerman is whether Roth treats his autobiographical sections as targets put up to be shot down by Zuckerman, or whether he wrote the sections in a genuine attempt to get back to the facts only to realize by the end that he had failed because failure is implicit in every attempted act of autobiographical retrieval of the past.

Besides, Roth appropriates "Josie" to his own autobiographical purposes in the course of the latter part of the book. To the extent that The Facts represents Roth's Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man Josie is made to serve as his bird woman or negative muse. Unlike her fictional counterparts in When She Was Good (1967) and My Life as a Man (1974), she is used in The Facts to represent the underside of life which Roth now claims he had to experience before he could discover the anger within him that enabled him to find his true métier as a novelist. He singles out her "bedazzling lunatic imagination" (112), her virtuosity as "a master of fabrication" (111), to account for his fascination with her: "Without doubt she was my worst enemy ever, but, alas, she was also nothing less than the greatest creative writing teacher of them all, specialist par excellence in the aesthetics of extremist fiction" (112).

Roth offers her here in the form of a paradox. Within the autobiographical text she has become a trope, a figure of language in a linguistic construct. He even refuses to call her by her true name. Zuckerman accuses Roth of relegating "Josie" "to a kind of allegorical role" by hiding her true identity (179). Roth is here discovering what De Man asserted to be the essential feature of autobiography - that like all textual systems it is made up of tropological substitutions that guarantee the impossibility of closure or totalization ("Autobiography as Defacement" 922). The real unrecoverable "Josie" has a textual stand-in and becomes a trope for negative inspiration. As Zuckerman concludes: "Her idealization is a necessity of this autobiography" (182). Zuckerman is only spelling out what Roth already realized as he was attempting to write his factual account of their relationship in section three.

The fourth section, "All in the Family," deals with charges of anti-Semitism and self-hatred that were levelled against Roth after his story, "Defender of the Faith" was published in the New Yorker in April 1959, and collected in his first book of short stories, Goodbye, Columbus (1959). As with his involvement with "Josie," one is most struck by his naivety in this episode. Anyone who has read "Defender of the Faith" cannot help but recognize the provocation that it is likely to offer orthodox Jews. That is not to argue that it is anti-Semitic. But it is inflammatory. Roth claims to have been taken completely aback at the outcry with which the Jewish press greeted it. After Goodbye, Columbus had won him two awards, he reports how he was asked to speak at Yeshiva University in New York where he was given a roasting by an enraged faculty and student body of orthodox Jews. The episode, he maintains, turned the angry young writer into one destined to be permanently embroiled in Jewish self-definition:

After an experience like mine at Yeshiva, a writer would have had to be no writer at all to go looking elsewhere for something to write about. My humiliation before the Yeshiva belligerents...was the luckiest break I could have had. I was branded (130).

To be "branded" like some helpless steer is to be consigned to what he calls a page before his "thralldom" - to be turned into an unwilling prisoner forced to defy his captors, the orthodox Jews. These tropes reflect the fifty five year old Roth's need to justify what he terms his "upping the ante in Portnoy's Complaint" and subsequent novels and confirm the fact that autobiography traditionally tells us more about the (usually aging) writer than about his earlier self. Zuckerman is quick to accuse his creator of trying to pass himself off as little more than an unwilling victim: "As though you still have no sense of how you were conspiring to make it all come about" (174). The facts are identical. But we are offered at least two mutually opposing ways in which to interpret them.

The fifth and last section, "Now Vee May Perhaps to Begin," derives its title from the last line of Portnoy's Complaint, constituting the first words to be spoken by the psychiatrist to whom the rest of the book is spoken. It is intended to suggest how his true life as a writer began with the end of his early life - the death of "Josie," the abandonment of his neo-Jamesian phase of writing in the high style, the end of his attempts to placate his Jewish compeers. So the end of his autobiographical narrative coincides with, and constitutes an account of, the beginning of his career as a scatalogical, embattled writer who announced his arrival on the literary scene with the publication of Portnoy's Complaint.

This section is far closer to the tone of Zuckerman's final letter to Roth. In part it consists of an in-depth analysis of the major ingredients that went into the make-up of Portnoy's Complaint. However Roth appears to be motivated by a desire to prove that the book had nothing to do with his own home life and parents. There were his new Jewish friends with whom he shared a taste for "recycling into boisterous comic mythology the communal values by which our irreducible Jewishnes had been shaped" (136). There was Lyndon Johnson who provoked "the fantastical style of obscene satire that began to challenge virtually every hallowed rule of social propriety in the middle and late sixties" (137). There was his seven year long psychoanaysis undertaken to counter "Josie's" demolition of his self-confidence, an analysis which "itself became a model for reckless narrative disclosure" (137). There were the attacks on him by his fellow Jews. And there was May, the new gentile woman in his life, whose tenderness highlit "the sort of tribal difference that would empower Portnoy's manic self-presentation" 137).

The sheer complexity of the personal threads out of which Roth says he wove Portnoy's Complaint gives much of this portion of the narrative an interest lacking in the simpler earlier parts. However when one remembers that Portnoy's Complaint was written in the form of a psychoanalytical monologue addressed to an analyst, and when one simultaneously reflects on the fact that Roth underwent seven years of analysis during the years covered by the central narrative, the fact that he only mentions it once in the main portion of The Facts draws attention to the highly selective nature of this record of his life. It is, as its subtitle suggests, "A Novelist's Autobiography.' It takes the form of an apology for, and explanation of, the kind of "extremist" fiction that he has produced since Portnoy's Complaint. Roth has Zuckerman light on this major omission in the autobiography, speculating whether the reason for Roth's passing over his long analysis in silence is not that "the themes [are] too embarrassing"(169). Seeing that the "reckless narrative disclosure" of his anaysis provided the fictional voice for at least one of his novels, he can hardly argue that it is not pertinent to his "Novelist's Autobiography." Once again Roth tries to have it both ways, omitting the analysis while using Zuckerman to fault him for doing so and thereby hopefully disarming the reader.

3

In January 1988 Roth

made a brief speech when he accepted the National Book Critics Circle award for

The Counterlife. In it he described the way the facts with which the novelist

starts are dealt with first by the imagination and then by the mind: "This butcher,

imagination, wastes no time with niceties: it clubs the fact over the head, quickly

it slits its throat, and then with its bare hands, it pulls forth the guts...By

the time the imagination is finished with a fact, believe me, it bears no resemblance

to a fact." When the imagination turns "this dripping mass of eviscerated factuality"

back to the mind, the mind promptly "sends down for fresh raw material, new

facts." The two are equally ruthless. The end product is a novel. Two kinds of

readers appear: "those who detest the severity of the mind and the violence of

the imagination...These readers are happy only with the facts - stupid as the

little facts are all by themselves - and so they strip away the imagination and

the mind of the novel to get to its factual basis." "Others, however, with a secret,

shameful but well-developed hunger for the brutality, cruelty and pitilessness

of imagination and mind, sit back and...cannibalize the flesh of fiction" (Roth,

"This Butcher, Imagination" 3).

In The Facts Roth offers the first class of readers a taste of what a book is like robbed of the ruthless operations of imagination and mind. The five central sections of the book are, as Roth tells Zuckerman at the beginning, "a distillation of the facts that leaves off with the imaginative fury" (7-8). What is left is a pale shadow of his fictional treatments of the same material. Roth appears bent on teaching his over literal-minded readers the difference between life and art, the facts and their fictional transformation. Throughout his life he has been plagued by readers who believe that his success in giving the appearance of life to what are ultimately just textual constructs is proof that his art is mimetic and that all he has done is to brilliantly reproduce the circumstances of his life in fictional disguise. Roth tells of the woman reader of Portnoy's Complaint who claimed to have known his sister when they were both at Weequahic High despite the fact that he had no sister - although Portnoy did (Roth, Reading Myself 40). Some critics of his latest novel, Deception, have still insisted on discerning Roth behind the protagonist, "Philip," and Claire Bloom behind the British female lead character. As he said to one interviewer, "To label books like mine 'autobiographical' or 'confessional' is...to slight whatever artfulness leads some readers to think that they must be autobiographical" (Roth, Reading Myself 17). One can see the main portion of The Facts as a prolonged exercise in educating this insistent kind of reader in the nature of fictional invention.

At the same time there does appear to have been a second and more personal motive for embarking on this quest for the facts, one triggered by his breakdown. It is possible that this latter motive weakened as the narrative proceeded. When the impracticality of the original project became apparent to him the didactic intention subsumed the therapeutic one. How else can one explain his continuing to write those five lack-lustre sections, even if interest does pick up somewhat towards the end? Deprived of the ruthless and outrageous operations of the imagination, the facts prove both banal and irretrievable. Maybe that is what Roth intended - a book-long demonstration of the conflicting and mutually destructive demands placed on the writer of autobiography. The autobiographer is expected to do the impossible, to be both an honest recorder of the past and a linguistic magician entertaining the reader with his imaginative insights. But the demonstration calls for too much patience from the reader. As David Denby, reviewing the book for the New Republic, concluded, it is "a negative accomplishment, like building a ship you know will sink in order to prove the weakness of the hull" ("The Gripes of Roth" 40).

Yet this ship doesn't quite sink. Because towards the latter part of the factual portion of the book the imagination begins to infiltrate the text, to bring it linguistically to life. As early as in the second section Roth shows considerable wit in the course of explaining why he chose a Jewish rather than a non-denominational fraternity at Bucknell. One small example. He asks, why the need for a specifically Jewish fraternity in the 1950s. The reason he offers is that the "Jews were together because they were profoundly different but otherwise like everyone else" (49). That enigma lies at the heart of much of his writing. It is worded so as to shock the reader into an awareness of the way Roth has chosen to use his ethnic background to investigate the experience of growing up as an American, since all Americans originate in some minority ethnic grouping or other. Considered factually Roth's use of paradox here amounts to a contradiction in terms. But life and art and language are full of such contradictions. For Roth the whole point of fiction's distortion of the facts is to "excite your verbal life" (Roth, Reading Myself 144), which is precisely what a sentence like the above achieves.

But what is it doing in an autobiography that claims to rigorously confine itself to the facts? Why does Roth end the book with Zuckerman's detailed analysis of the numerous occasions on which Roth fails to give all the facts or to tell them straight? The answer lies in the reflexivity of this book. It circles about itself. Ultimately it is about itself. It is an exercise in, and a meditation on, the nature of the autobiographical act. It shows Roth coming to terms with the fact that he is a writer who, like all writers, cannot escape from the disseminating nature of language which lures him into the labyrinth of textuality. To narrate is to select, to rearrange, to codify, to transform the original experience. "It's through dissimulation," Zuckerman tells Roth, "that you find your freedom from the falsifying requisites of 'candor'" (184). The entire book is a highly fictive artifact. It is framed by imaginary letters to and from a fictional character. At least two of its five sections start in media res as so many stories have since Homer's time and before. It is filled with references to other texts

In fact Roth makes extensive use of intertextuality both in the titles of the book and of its individual sections, in its epigraph (from The Counterlife ), and throughout the main body of the text. As Ralph Baumgarten pointed out in his review of The Facts the title of the book parodies the world of "Dragnet," Jack Webb's radio and television show, in which the detective asks a character in each episode for "the facts, ma'am, nothing but the facts." The same playful referentiality applies to the titles of the five episodes. "Safe at Home" is a baseball term, "All in the Family" the title of a popular television sitcom, "Joe College" and "Girl of My Dreams" are both narrative clichés, and "Now Vee May Perhaps to Begin" a quotation from an earlier novel of his. In each case Roth gives an ironical twist to the traditional connotations of the well known phrase. To cite one instance, "All in the Family" concerned the working class family of Archie Bunker, a tremendous racial bigot among other things. But the family to which Roth alludes in the section of that title is the world family of Jews, some of whom turn out in his account to be just as prejudiced as Archie was. In each chapter there is a similar ironic tension between the expectations set up by the conventional title and the outcome of such expectations (shared by reader and protagonist) in the body of the episode. Roth as author seems to be illustrating in this way how the text of his life can only be rendered in terms of the texts of other fictional lives.

Intertextuality also operates between different portions of the book. Zuckerman's long letter at the end deconstructs the rest of the book, recasts The Facts as meta-autobiography, forcing the reader to think back over the main portion of the book and reflect on its inadequacies as a record of the facts concerning Roth's life. The concluding letter compels the reader to acknowledge the necessity of employing fictional and fictive devices in all forms of autobiography. Zuckerman is a wholly fictional device, a persona borrowed from Roth's most recent novels to represent the carnivalesque element that has characterized all his fiction since Portnoy's Complaint. Roth begins The Facts by attempting to get back at the artist lurking behind his art. He ends by incorporating Zuckerman and Maria, personifications of his art, within The Facts. Fiction cannot be excluded from the genre of autobiography, which, because of its pretensions to greater factuality, is, as Zuckerman asserts, "probably the most manipulative of all literary forms" (172).

It has been shown how almost every objection that the reader is likely to raise against the main portion of the book is raised by Zuckerman, Roth's other voice. For it is, of course, Roth who is speaking as Zuckerman as much as in his own person. One of Roth's more brilliant strokes is to give Zuckerman an exuberance and skepticism that makes his voice the more authentic of the two. In his concluding letter Zuckerman progresses from a concrete critique of the main portion of the book to a reassertion of his fictional reality. Roth appears to be showing how this character of his invention with his newly acquired beard is as much a part of Roth's fugitive identity as is the elusive figure he tries to establish in the main portion of the book. Both are textual artefacts, verbal combinations of traits, but Zuckerman is a much more convincing verbal construct than is "Philip Roth."

Is Roth using Zuckerman to limit the reader's choice of interpretations? Does Zuckerman's alternative version of the facts exclude other possible versions? Roth anticipates this accusation by introducing Maria, Zuckerman's fictional wife, whose different reactions to reading Roth's manuscript are recounted by Zuckerman in the final portion of his letter. Maria, as we know from Roth's previous fiction, could not be more different from Zuckerman. Where he is Jewish, male and American, she is gentile, female and British. Where Zuckerman shares Roth's liking for confrontation and scandal, she is all for the quiet life. Her distrust of Zuckerman's three-month-old Jewish-looking beard is on a par with her critical reactions to The Facts: "'Uh-oh,' she said, only minutes into the book, 'still on that Jewish stuff, isn't he'" (188)? Roth employs Maria as a touchstone for instinctuality. He has her criticize him for his obsession with the Jewish experience, for his typically American identification of his fate with his freedom, of a lack of randomness in his ordering of the facts. Seen through her woman's eyes his marriage was the result of his weakness, and he betrays a typical man's distrust of all women throughout the book. Maria too is Roth's fictional creation, the spokesperson for his anima or Other. How can that persona be expressed through a narrow rendition of the facts? Roth, then, is not just the sum of "Roth" and Zuckerman. Maria offers a third perspective from which to critique the versions offered by both "Roth" and Zuckerman. The implication is that Roth could go on proliferating these perspectives indefinitely. There can be no full closure in autobiography.

But artistic closure of some kind is required. After Maria has had her say, Roth has Zuckerman play out one final confidence trick on the reader. Zuckerman concludes:

...the book is fundamentally defensive. Just as having this letter at the end is a self-defensive trick to have it both ways. I'm not even sure any longer which of us he's set up as the straw man. I thought first it was him in his letter to me--now it feels like me in my letter to him (192).

At a stroke Zuckerman undermines his reality as an authentic voice and confesses to his pseudo-existence as Roth's ventriloquist dummy. His seeming freedom to vent his criticisms of the book are exposed as the artful strategy of the author attempting to forestall his reader's every objection. Roth, the recorder of the facts, first employs a fictional persona to strip them of their factuality and then strips his fictional persona of his fictional reality. What is left? The pervading presence of a polyvocal writer who can only express his many-voiced self through the many voices of his fictional inventions - the voice of the novelist. Roth uses Zuckerman, his fictional mouthpiece, in the closing words of the book to declare in favor of the novelist who has already enmeshed the facts of this book in his fictive verbal web:

Having argued thoroughly against my extinction, in some eight thousand carefully chosen words, I seem only to have guaranteed myself a new round of real agony! But what's the alternative (195)?

Clearly not the facts.

Works Cited

Baumgarten, Ralph. "The Life of Philip Roth, or,

Zuckerman's Complaint." Rev. of The Facts, by Philip Roth. Los Angeles

Times Book Review 11 Sep. 1988: 1+.

Benveniste, Émile. Problems

in General Linguistics. Trans. Mary Elizabeth Meek. Coral Gables, Florida:

U of Miami P, 1971.

Blanchard, Eli Marc. "The Critique of Autobiography."

Comparative Literature 34.2 (1982): 97-115.

Brent, Jonathan. "What

Facts? A Talk With Philip Roth." New York Times Book Review 25 Sep. 1988:

3+.

Denby, David. "The Gripes of Roth." Rev. of The Facts, by Philip

Roth. New Republic 21 Nov. 1989: 37-40.

De Man, Paul. "Autobiography

as De-facement." Modern Language Notes 94.4 (1979): 919-930.

Milbauer,

Asher Z, and Watson, Donald G. Reading Philip Roth. London: Macmillan P,

1988.

Roth, Philip. Reading Myself and Others. New York: Viking Penguin,

1985

--- . The Facts. A Novelist's Autobiography. New York: Viking

Penguin, 1989

--- . "This Butcher, Imagination: Beware of Your Life When a

Writer's at Work." New York Times Book Review 14 Feb. 1988: 3

Weber,

Katherine. "Philip Roth." (interview) Publishers Weekly 26 Aug. 1988: 68-69

Copyright 1993 Brian Finney

http://www.csulb.edu/~bhfinney/Roth.html

Deciding to Do the Impossible

By WILLIAM

H. GASS

THERE have been thousands of different drawings of the world, many maps made of reality. Each puts the gods, the good, the false and the true in a different place. They cannot each be correct - there are too many counterclaims - yet society after society has sailed to greatness (not simply to the doom they also doomed themselves to) following these false charts, these fictions that have been projected upon the planet. And the planet, like the great screen of a drive-in movie, accepts them all, lighted by the illusions of passion, for as long as the passions last. If so, then our lives are made of fictions, beliefs we construct and then dwell in like a beach house in Malibu. When we change our life - one of the central themes of Philip Roth's magnificent new novel, a remarkable change of direction itself - we recreate "a counterlife that is one's own anti-myth," as Roth's protagonist, Nathan Zuckerman, surmises.

"Nothing is impossible," declares Mordecai Lippman, the fanatical Zionist of the novel, who, like the phoenix, practically invents himself out of ashes and heat. "All the Jew must decide is what he wants - then he can act and achieve it." But first of all you must become a Jew, a root Jew, not merely a branch Jew like some bank in the suburbs. In novel after novel, Roth has asked what Jews want with somewhat the same irritated bewilderment we associate with Freud's question: "What do women want?" In "The Counterlife," the query has become more riddling, more radical and, despite the antic flipflops of the plot, more serious yet no less witty for all that: can a Jew, if he wishes - if he wants -change into a Jew? And in what direction should he go to do that? And why should the quiet course of a comfortable life be shattered by such questions, which were always there to be put, but were answered by not being asked? And is not the anti-Semitism of a Jew the refusal of a Jew to be one?

These are a few of the questions Philip Roth's latest novel considers, turning them round like meat on a spit. With respect to his own past as an author, there are many questions - the hedges, qualifications, objections entertained by critics - to which it gives a resounding answer. "The Counterlife," it seems to me, constitutes a fulfillment of tendencies, a successful integration of themes, and the final working through of obsessions that have previously troubled if not marred his work. I hope it felt, as Roth wrote it, like a triumph, because that is certainly how it reads to me. THE style is a triumph too. It is no longer a style at war with itself, as Roth's sometimes used to be, its cleverness undercutting its own emotions, its satire thinning a subject already sliced. Its combativeness is no longer pointed at the reader, the critic, the family or some other ancient adversary. The world of "The Counterlife" is made of intelligent, argumentative, witty, observant words. They are words woven now, after the practice of many years, into a rich, muscular, culturally complex style that even in purely narrative moments seems to come not from the end of a pen but through the flow of the voice, thus from a mouth - the organ that Zuckerman's brother, a dentist, seductively describes, for the young assistant he is about to hire, as genital. It is surely the opening through which, to continue life, the world is received. It is also, quite as surely, the loudspeaker of the soul. And in "The Counterlife" a lot of those loudspeakers are on. Full blast.

The book comes to us wrapped in more than its dust jacket. It continues and seems to conclude a series of affairs, ambitions and other anxieties taken from the life of Nathan Zuckerman; a life whose telling began before its tolling in "The Ghost Writer" of 1979, and which, after two more novels, "Zuckerman Unbound" in 1981, then "The Anatomy Lesson" in 1983, was advertised as ending in 1985 with the addition of a novella, "The Prague Orgy," so that the entire collection could be called "Zuckerman Bound," a volume you were encouraged to buy in the belief that at last you had hold of the whole thing. So our present text is legitimately preceded, if not surrounded, by the four books that carry the Zuckerman name to this point.

However, Roth would now have us believe that Nathan Zuckerman is the invention of Peter Tarnopol, the professor and novelist of "My Life as a Man." Tarnopol endeavors to come to some understanding of himself by composing a series of fictions that are then topped off by the real thing, Tarnopol's autobiography (which we should no more believe is true of Tarnopol than "My Life as a Man" is true of Roth). And this conjunction of fact with fancy presumably allows us to estimate the alterations imagination makes to any fictionalized biography. In a Roth novel, it is not unusual for characters to cross from one text to another as though they were crossing a street. Dr. Spielvogel, the psychiatrist of "My Life as a Man," is also the analytic ear listening to Portnoy's complaint.

Nathan Zuckerman is the author of a notoriously dirty book, an alleged libel of the Jews, "Carnovsky," which has made him both rich and reviled, just as "Portnoy's Complaint" made Philip Roth well known, well off and the target of slings. So if we follow this tangle from head to tail, we shall discover that Roth has created a character, Peter Tarnopol, who has in turn invented Nathan Zuckerman, who has, for his part, written the same book Roth has (since "Carnovsky" equals "Portnoy"). This ring of real and fictive authors puts us at least a touch back, if not smack back at the beginning. It is consequently not stretching the facts but admitting them to say that "The Counterlife" is both thematically and structurally connected to the general body of Philip Roth's work.

Nor is this all. One of Philip Roth's preoccupations as a writer has been the relation between "his life as a man" and "his life as a character"; between life in the world and life in his fictions; between the fictions Roth reads and the fictions Roth writes. Both the life and the work of a writer like Kafka are as real and resounding to Philip Roth the writer as any other element of his material. When Zuckerman imagines that a young woman he has just met and immediately fancies is not the ghostly author of "The Diary of Anne Frank," but Frank herself (a survivor as well as a victim of the camps, who has continued to play dead to enhance the influence of her book), we are not dealing simply with the perhaps absurd obsession of a character in a fiction.

The Zuckerman books are full of warnings to their readers about the differences, subtle sometimes, between real life and art: "They [ those affected by the sex-mad Carnovsky ] had mistaken impersonation for confession and were calling out to a character who lived in a book." Zuckerman's anguish over this error is expressed too eloquently and too often to be merely his. But now we have crossed the line to lay the attitude of a fictional figure at its author's feet.

If "the artist descends within himself," in those words of Conrad Zuckerman approvingly quotes, "and in that lonely region of stress and strife . . . finds the terms of his appeal," then Roth does not go down so deeply that he loses sight of the salient facts of his life. His personal problems, particularly successes and sufferings, continue to preoccupy him. What Conrad clearly expected the artist to do was to descend beyond those particularities to a place where pride and anxiety and stamina and weakness could find new terms for their expression - locate the general, not the local, source of their appeal. DESPITE the author's disclaimers, the many parallels between the Zuckerman saga and the Philip Roth story invite the confusion. Part of "The Anatomy Lesson," for instance, is a vengeful reply to a particularly stinging critical piece on Roth by Irving Howe. The identity of Howe is hidden like a lamppost in the living room. Another section is concerned to rebut the feminists. A reader ignorant of Portnoy's habits, unfamiliar with the critical climate, a reader for whom the author's name is merely that - short, an off rhyme with wrath - would be blessed by such ignorance, and possibly able to see the book, because this new work, like each of the others, is not only wrapped in Zuckerman and Tarnopol, it is also wrapped in Roth.

If you are a black writer, professional blacks (that is, people whose business is being black and little else) will require blackness of you, although each critic may favor a different shade; and if you are a woman, the feminists will make analogous demands, and hunt through every page looking for the incriminating pronoun and other signs you have succumbed to something macho; and if you are a Jewish writer it will be the same, though the quarreling groups will perhaps be more numerous and have been at it longer. Philip Roth has been praised by this group and damned by that, and charged and vindicated and hailed and cursed by readers whose real interests were as far from literature as fanaticism will always take you - to the opposite pole. It is a pole Roth stirs them up with.

So the Zuckerman chronicles continue. Nothing is changed. Every old quarrel has a home in this text. There are references, naturally, to previous books. We are still teased by details taken from the author's life and we are encouraged to search for more, while at the same time the fundamental connection is denied. Sexual expression, phallic power, oral fixation: each is present. Family oppression and familial duties: these too. But above all, there is the presence of the question of what it means to be a Jew. Nevertheless, everything has changed after all. These themes no longer possess our author. He has become their master.

The book begins with the brother's death. Henry, the dentist, has heart trouble. The medicine he is taking for it makes him impotent. Unable to sport with his hygienist any longer, Henry grows desperate and undergoes a bypass operation that will remove him from his medicine, restore his manhood and incidentally repair his heart. His wife chooses to believe it is for her he has run this risk. But soon Roth will skillfully split the narrative. Henry will unaccountably recover from his death at the hands of the text, and with his revived heart will hasten abruptly away to Israel to take up righteousness and seek the faith. There he will carry a pistol and develop a different, more martial, manhood. It is not heaven he has gone to but Judea. It is not the West Bank he has gone to, but War.

We learn that Nathan Zuckerman, Henry's nemesis, has refused to speak at his brother's funeral. For reasons, of course. Well, wait. Henry will get his opportunity to refuse to speak at Nathan's. These are counterlives but suspiciously parallel tales: woman against woman, marriage against marriage, both or neither brother surviving the knife, as the novel continues its surprises. For Nathan's story could be said to commence with his death, too, at a later date in the text, though from similar causes and resembling motives. Nathan has the same punning problem - a troubled heart -with its emasculating consequences, which means he cannot marry the sweet young object of his present affections and beget the child he finally thinks he wants. So he too will seek a remedy beneath the surgeon's knife and receive his quietus for it.

First, Tale One must wag. (But both may belong to the same dog.) We follow Nathan as he follows Henry to Israel. There he receives doses of rhetoric from every mouth sufficient to cure complacency by killing it. Hope is killed as well. The European Jew speaks, the radical right-wing Jew speaks (he also speaks for the Arabs so as to have some worthy opposition). The anti-Semitic Jew speaks, the peaceful Jew speaks, the Furies have their innings. Like sound trucks in the street, through Nathan they holler wonderfully at one another. The arguments concern Jews, are about Jewishness, about power, and are wholly political. The political and the moral are artfully confused. So this is not a novel about ideas only, but about beliefs - those beliefs that, like bombs, we daily drop on one another. The speakers' rhetoric is their rifle. And the characters establish their character by means of their speech, through the defense, the advocacy, the oppressiveness of their opinions.

This speech does not turn back upon itself as Stanley Elkin's often does, nor are its rhythms so obviously Yiddish as Bernard Malamud's sometimes were, nor is it quite as continuously civilized as Saul Bellow's. It has an insistently forward push toward the next thought, the next feeling, a future desire; it does not normally dawdle in description, or stop for meditative poesy, or paralyze its movement with refinements and indecisions. In this it is urban, male (no matter the sex of the speaker), quick, artful yet blunt, overbearing, mean, street smart but worldly wise. In each case, it seems superb for its purposes and complete.

Every belief is buttressed, not with reasons, but with the crimes of opponents. The gentiles have done thus and so; the Arabs, also, have done thus and so; therefore we, the Jews, should do thus, and thus, and thus and so. Action follows action like an avalanche of rock. Of course resentment stretches as far as one can see sand. And every Jew, except for the secular, corrupt, pluralistic and skeptically minded Nathan, believes it essential that every Jew believe the same as every other Jew, achieve the solidarity of the Wailing Wall. The speeches which give air to these opinions are intensely interesting, passionately convincing and perfectly phrased. Although each view is by its fevered nature a partial one, such is Roth's skill that the accumulation of these partials makes for an impressive whole. UNARGUED lives may also be worth living, but you won't find them in this book. The two brothers continue to counter each other, appear to oppose each other, as the geography of the novel does, locating some of its scenes in America, others in England's green and pleasant land as well as in the deserts of Judea. Nathan's new love lives in London, and this permits Roth to parallel the book's vivid earlier scenes at the Wailing Wall with Christmas caroling in a cathedral. He lays the complacent, stupid, almost serene anti-Semitism Nathan confronts in Gloucestershire alongside the louder, less secure dislike for the goyim he finds in Israel. And finds in his brother. And finds in himself, for he is, of course, his brother - at least by now. He has accepted his brother -American middle-class dentist one moment, Israeli militant another - in order to continue to live. Live what? A fictive life?

Each often painful encounter with these examples of Jewish love and Jewish hate has cleansed Nathan Zuckerman, who has sought the solution to his nature through book after book, of one more trapping of his type, until he finally sees himself as "a Jew without Jews, without Judaism, without Zionism, without Jewishness, without a temple or an army or even a pistol, a Jew clearly without a home, just the object itself, like a glass or an apple." Except for the phallic scar, the venereal voodoo he desires to have performed upon his son - a futile mark of difference, it would seem to me, since circumcision is now more fashionable among the gentiles than pierced ears. A LITTLE past its middle, in a brilliant postmodern maneuver, the book becomes posthumous, and begins reading itself both front and rear, before and after, like a swing. With Nathan dead of Henry's heart, Henry seizes and censors the manuscript of his brother's latest book. It is a draft of "The Counterlife." Our surprise at these developments, and a number of others, is honestly accounted for by the structure of the book and brilliantly brought off each time. I think the novel's daring shape will continue to possess its fascination for us upon a second look, a third reread, just the way the turns in Haydn's "Surprise" symphony still delight us.

When a woman becomes a character, not a lover or a wife; when this character expresses her desire to leave the work the way she might a husband; when goy and galuth quarrel over, of all things, circumcision; when we remember, as good readers ought, what St. Paul said it took to make a Christian: a faith in Jesus as the Saviour that (not to hold back the knife) was the equivalent in spirit to the circumcision of the heart; and when a man (a character) who is already dead when we read the words that render his forthcoming life is heatedly arguing with his wife about one more operation, insisting that the paper tale we've been passing through in their company is "as close to life as you, and I, and our child can ever hope to come"; and when we know, or think we know, that Zuckerman, now only ashes, wrote his own maybe-marriage with its male offspring and the boy's disputed penis into being the way he wrote his own funeral eulogy; when we realize that Zuckerman himself is Tarnopol's creation, and that Tarnopol lives only in another book by Roth, and that Roth, too, in the guise of Portnoy, Zuckerman and others, is in this same work as well, thrashing around; then we may be willing to agree that all of them have changed their nature right in front of us, passing, as it were, behind the page like a cloud; but such is the rightness of the form, the richness of the theme and the eloquence in the execution of this splendid novel that we can assent to the conventions, to the fiction, to the disclaimers and the harmless piles of paper it after all comes to, and still feel the words, still be moved and still care.

Don't Try to Get to the Bottom of Things The following excerpt is from a recent interview with Philip Roth by Asher Z. Milbauer and Donald G. Watson, which appears in "Reading Philip Roth," a collection of essays they have edited to be published later this year by St. Martin's Press.

We realize that you are reluctant to appear to be explicating a book prior to its publication. However, without "explaining" it away, can you comment generally on the unusual form for "The Counterlife," which is certainly unlike anything you've done before?

Normally there is a contract between the author and the reader that only gets torn up at the end of the book. In this book the contract gets torn up at the end of each chapter: a character who is dead and buried is suddenly alive, a character who is assumed to be alive is in fact dead, and so on. This is not the ordinary Aristotelian narrative that readers are accustomed to reading or that I am accustomed to writing. It isn't that it lacks a beginning, middle and ending; there are too many beginnings, middles and endings. It is a book where you never get to the bottom of things - rather than concluding with all the questions answered, at the end everything is suddenly open to question. Because one's original reading is always being challenged and the book progressively undermines its own fictional assumptions, the reader is constantly cannibalizing his own reactions.

In many ways it's everything that people don't want in a novel. Primarily what they want is a story in which they can be made to believe; otherwise they don't want to be bothered. They agree, in accordance with the standard author-reader contract, to believe in the story they are being told - and then, in "The Counterlife," they are being told a contradictory story. "I'm interested in what's going on," says the reader, "only now, suddenly, there are two things going on, three things going on. Which is real and which is false? Which are you asking me to believe in? Why do you bother me like this!" l or equally false. Which are you asking me to believe in? All/none. Why do you bother me like this? In part because there really is nothing unusual about somebody changing his story. People constantly change their story - one runs into that every day. "But last time you told me . . ." "Well, that was last time -this is this time. What happened was . . ." There is nothing "modernist," "postmodernist," or the least bit avant-garde about the technique. We are all writing fictitious versions of our lives all the time, contradictory but mutually entangling stories that, however subtly or grossly falsified, constitute our hold on reality and are the closest thing we have to the truth.

Why do I bother you like this? Because life doesn't necessarily have a course, a simple sequence, a predictable pattern. The bothersome form is intended to dramatize that very obvious fact. The narratives are all awry but they have a unity; it is expressed in the title - the idea of a counterlife, counterlives, counterliving. Life, like the novelist, has a powerful transforming urge.

January

4, 1987

http://www.nytimes.com/books/98/10/11/specials/roth-counterlife.html

Conversations With Philip

By DAVID PLANTE

David Plante is an American writer from Providence, R.I., who has lived abroad since 1966. His recent books include "The Woods," a novel, and "Difficult Women," a memoir of his friendships with Jean Rhys, Sonia Orwell and Germaine Greer. He met the novelist Philip Roth in 1975 in London, where Roth and the actress Claire Bloom live half the year. Plante, who lives there with the Greek poet Nikos Stangos, is collaborating with Roth in adapting the Jean Rhys section of "Difficult Women" for film; they would like Miss Bloom to play the role of Jean Rhys. What follows are excerpts from David Plante's diary that record hisfriendship with Philip Roth.

June 6, 1981

Philip telephoned today to say he's back in London. I hadn't known he'd gone - suddenly, because his mother died. He says he couldn't look at her body. He didn't want that meaningless image to obliterate all the images that matter. During the two weeks he spent with his father after the funeral he took notes. He's still taking notes. I said, "What kind of people are we? We don't even stop taking notes at a funeral." "Good enough." "Are we?"

Aug. 23, 1981

Connecticut. On the outside, Claire is still, then a quick gesture, like taking a hand from the steering wheel and passing it through her hair, will reveal all her inside movement. Her eyes calm, her bright black hair seems to swing of itself. She turned off a country road and through an apple orchard to a dark gray clapboard house shaded by big, old maples. Philip appeared with his father, Philip tall and lean, his father shorter and squarer, both wearing straw hats. Claire disappeared. When Philip smiles, he presses his lips together as if barely suppressing his amusement, and you don't quite know what his amusement is. It occurs to me that he is always trying to contain his expressions, large and on the point of going off in peculiar directions, so his face and even his body are kept composed. He says, "So the New England boy is back," but you feel he could have said a hundred other things, and what he could have said, but didn't, amuses him. A spark in his eyes, behind his rectangular, gold-framed glasses, is like a spark off his amusement. I said, "Me? I'm just a Canuck." I was sure he wanted to say more, but he pressed his smiling lips together. He didn't say, as I wanted him to, that he was just a boy from Newark, New Jersey. He told me I would stay in his study, which he pointed to across a lawn - a gray cottage with a screened-in porch. Philip left me with his father, who waited while I changed into a bathing suit, then, linking his arm in mine, guided me to the pool. He asked, "Are you married, Dave?" I said I wasn't. "You should be," he said. "You should have a girl like Claire, a nice fellow like you." He continued to talk as I swam back and forth in the pool. As I climbed out, he ran for a towel to hold it open and wrap it around me. I told him I was sorry about the death of his wife. "A wonderful woman," he said, "a really wonderful woman, Dave," and he turned away as his face gave way to his grief. He is much more expressive than his son. He is 80, was married for 54 years. He, Philip and I sat in the living room. Claire did not want help in the kitchen. Philip said, "I just finished reading Updike's 'Rabbit Is Rich' in proof. He knows so much, about golf, about porn, about kids, about America. I don't know anything about anything. His hero is a Toyota salesman. Updike knows everything about being a Toyota salesman. Here I live in the country and I don't even know the names of the trees. I'm going to give up writing." His father said, "Bess and I always said we were proud of Philip's writing. Anyone ever called us up, we'd say, 'We're very proud of our son,' that's all." After supper, Roth went into another room to watch television, and Philip, Claire and I talked about giving up our careers to become, as Philip insisted, doctors. Claire wanted to be a pediatrician. Philip said, "I'm going to be an obstetrician." I'd be a gynecologist. On my way back to the cottage, Philip said, with his smile, that I could look through the papers on his desk, in his files. "Love letters under L." Alone, I looked around carefully, thinking: I must recall all this - the photograph of Kafka, the drawing by Philip Guston of Philip (Roth, that is) with black beard stubble. Perhaps he did mean that I could look through his papers, and yet perhaps not. Without touching them, I studied the pages of yellow foolscap on his desk; most sentences were crossed out, and all were illegible. There was only one I could make out alone on a sheet: "How many Jews can dance on the head of a pin?" Then I turned to his large metal files, and a curious self-consciousness came over me - not only that of a younger writer in the study of an older (not that much older) and renowned writer, but that of the younger writer having read in one of that renowned writer's novels a scene similar to the one in which the younger writer finds himself. Did Philip think of this when he put me in his study? What was odd was that I enjoyed this self-consciousness - enjoyed it without thinking I was being false, because the scene was already made real, made true, by its appearance in "The Ghost Writer." At breakfast, Philip's father talked a lot about friends in Newark - who'd married, who'd had babies, who'd died. Claire was quiet. I asked questions. Philip brought to the table a long, rolled-up photograph and spread it out; his father held one side, I the other, and Philip, standing, pointed to members of a family convention at a hotel in Boston in 1948, where about 200 people were sitting around tables in a paneled dining room with chandeliers and Turkish carpets, and all the people were facing the camera and smiling. Philip didn't make jokes, as he usually does; he spoke with a quiet seriousness. At the very back were his father and mother, she with a long, white, beautiful face. Philip was not present. Claire quietly left the room. I said to Philip, "You've got to work." "I do," he answered matter-of-factly. He came with me to his study, where I'd left my bag. "Let's talk a while," he said. On the screened porch, we looked out on a wall of gray, lichen-covered boulders and birch trees beyond. He said, "If you were with my father a month, he'd have you married. He'd find even you a girl, David. You'd have to fight her off." "I'm sure your father knows the right thing for me." We talked about our families, openly and in great detail. Philip said to me that people are too easily shocked. "A little less shock, a little more curiosity." Back in the kitchen, Claire was making out a shopping list. Philip's father went out. Philip and Claire argued about the shopping. They were silent for a moment, then they finished the list together. Before I left for New York, Claire and I had a walk along the river. She wore a red dress with green and yellow Mexican embroidery and a straw hat. I asked her about her life. Sometimes we stopped on the path to watch the river. She said that before she met Philip she was incapable of protecting herself because since she was 17 everything was taken care of by others - agents, lawyers, producers, etc. Then suddenly she found that some of those who had been taking care of her had taken her for a ride. She was very low. Philip changed her life, saved her - toughened her up. She asked me about Nikos. I felt close to her, and at the bus stop, I embraced her with a kind of understanding closeness. The fact is, I don't know Claire and Philip.

Feb. 10, 1982

Philip and I were standing on a corner in Notting Hill, by a red mailbox. I saw an Englishman I know come toward us in a crowd, but he didn't see us and passed us by. Philip was talking, leaning toward me. He has been talking a lot about his mother's death. When he is keen, his nostrils contract. He stops talking, and his eyebrows, too, contract. I always take the first step to get us going. As we walk, he talks, much more than I do, and much more intensely.

Feb. 21, 1982

The last time we met, Philip talked of real stuff in writing and gave me this, written on a torn sheet of paper, to think about: "You must so change that in broad daylight you could crouch down in the middle of the street and, without embarrassment, undo your trousers." I forget now where the quotation is from, some 19th- century German author, I think. Philip added: "The emphasis is on the word could. Not that you would, because you wouldn't. But you should be capable of doing it."

March 25, 1982

In his study, Philip said, "Updike and Bellow hold their flashlights out into the world, reveal the real world as it is now. I dig a hole and shine my flashlight into the hole. You do the same."I said that I long to write about the moment I'm living in, as in my diaries. In my fiction, I'm still an adolescent, learning about a world that's now 20 years old. We went out to supper in a restaurant with white tablecloths and white napkins peaked on white plates. He asked me if I think often of death. "For some reason," I said, "death reassures me. It can't be faked." "Oh, no," he said, "you can't be reassured by that." "I shouldn't be." "Yet I'm sure of the final doom," Philip said with that quiet seriousness I got used to. "The nuclear holocaust is well on its way." "And that reassures my dark soul." "What is your dark soul?" he asked brusquely. "My sense that what is true is that everything is fated for destruction and there is nothing we can do about it." "There is a devil, isn't there?" I laughed. "Now I've become rather dark myself," he said. "I'm sorry." "Can you write when you're in a dark state?" "Yes, I can." "I can't. I have to write from a lively state." Oh yes, this: we mixed up sexual obsession in our talk about doom. I said I was less and less obsessed, and it is a relief. He said, "I'll be obsessed when I'm 80 exactly as I was when I was 18."

April 6, 1982

A few days ago I telephoned Philip to invite him and Claire to dinner. He said they couldn't make it, and I was relieved - I suppose because I am self-conscious when with them. But I went on saying how much I wanted to see him and Claire. After I hung up, Nikos said, "You were utterly false. Utterly insincere." I groaned. "I know." "Your niceness toward Philip was completely unconvincing." "To him?" "I know what you try to do - you try to show him you're open to admitting anything about yourself, whatever it is. Well, you've got to be open, but not because you think he's only interested in you if you are. I thought you'd reached a point where you could be bold with people." "What shall I do?" "Be aware. You're intimidated by Philip." "I am."

May 10, 1982