Back to intro or goto next section or goto dam update page

The Dams of Redridge

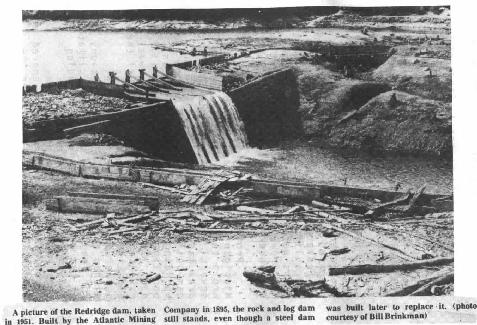

A stamp mill requires water for use in the "wash" of it's operations to

separate the copper mineral from the rock it was mined from. One of the

reasons the Atlantic mill was placed in Redridge was the fact that it had

a stream, the Salmon Trout River, that could be dammed up and used to

supply water for their mill. The first dam constructed on this site was a

timber crib dam built of timber, loose rock and earth. The main portion is

53 feet thick at the bottom, 28 feet thick at the top and 50 feet high.

The length across the stream is 51 feet at the bottom, 228 feet at the top.

The timbers were 14 inches thick and hewed flat, bound together with

inch square drift bolts. The upstream face was lined with four inch plank,

which was then covered in 2 inch plank. An earthen embankment was

constructed on the inner side of the dam with a slope of 1.5 to 1. When

referring to the earthworks of this dam, the word constructed is somewhat

of a misnomer. All of the work on this dam was done by hand, no heavy

construction equipment was available, so all of the dirt was literally

shoveled into place. At the base of the dam, near the east bank of the

river, there were two cast iron pipes 24 inches in diameter with gate valves

placed about 170 feet back from the toe of the dam. These gates were

then closed to allow the dam to fill. The water was transported from dam to

mill via a launder 18"X36" in cross section, 2050 feet long and dropped

5 inches per 100 feet of length.(25) The cost to Atlantic Mining Company

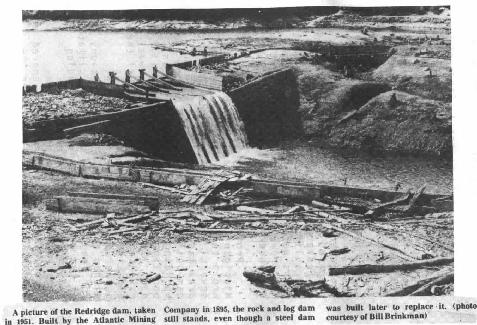

for the dam was a total of $24,161.58. Below is a picture of this dam

as it looked in 1951 after the steel dam had been drained.

The current picture of this dam may be seen at the top of this section.

An intriguing feature of this timber dam is the offshoot of the dam just to the west of

the main portion. It can be seen in the 1951 photo on the right side of the dam.

It took a long time for this researcher to come up with

a reason why it is there in the first place. The area behind this part of the

dam does not look like it would have held back water very often. There is a

large depression several feet behind it, but it is not currently connected to

the rest of the old reservoir that the old dam still holds. The diagram of the

Atlantic site from the 1895 Atlantic stockholder report

shows water behind this portion, though it is possible that this area was filled in somehow during

construction of the new dam or by deposits while it was submerged behind

the new dam. The answer comes when one looks at the 1951 picture,

and then at the Redridge site plan. The small channel that this

downstream of this portion is angled in such a way to suggest that it is where the small creek

coming from the west emptied into the Salmon Trout River.

Reports from the Atlantic Mining Company in 1900 stated that the crib

dam was showing signs of weakening(26) and since Baltic Mining Company

was in the process of building it's own stamp mill at the site, a new larger

dam was to be constructed so both mills would have enough water to operate.

Horace Stevens in the Copper Handbook of 1900 "The peculiar conditions

prevailing at the mouth of the Salmon Trout rendered a dam of ordinary pattern

almost out of the question."(27) They were peculiar in that there were no

nearby sources of stone for a masonry dam, and the site was far too remote

to haul in the materials necessary to build a regular dam. Also,

copper prices had boomed in the years since Atlantic Mine first built their mill,

so the companies could not wait for a conventional dam, especially with such

short construction seasons that are typical to the area. Atlantic and Baltic mills

needed something fast, and so they decided to try a new technology, steel dams.

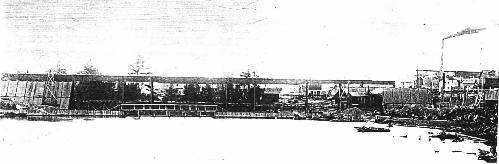

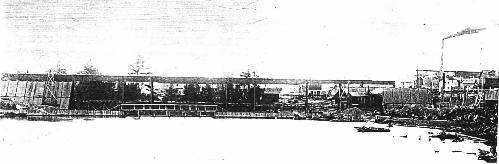

The photo above shows the dam in early phases of construction.(28) The steel portion of this dam is 464 feet

long(29) and at it's central portion is 74 feet tall. The steel portion of the dam is

flanked by concrete core earthen embankments on each end to stretch the total

length of the dam to 1006 feet. Water was taken from the dam through three

valves near the ends of the steel structure 20 feet below the crest. Sources of

information on this feature of the dam vary somewhat as to what dimensions these

were. Company reports do not mention it, Copper Handbook lists 38 inch diameter

pipes, Engineering News listed 24" valves(30).

Personal  examination of the remains

of the Atlantic feed (photo at right) shows that this particular pipe is 24" in diameter.

The size

of the pipe leading down to the Baltic is also contradicted by the Sanborn maps of

that facility, which list one 36" diameter pipe leading into the mill instead of a 38"

pipe reported in the other sources. In the original writing of this report, I was unable to

measure the baltic pipes because they were buried in snow. But on a trip back there in

October 1997 I was able to take the photo below. What I found was a diameter changing

fitting with a cleanout in the middle. The left side of the fitting measured 24", and the right side

measured 38" (both outside diameters)(31)

examination of the remains

of the Atlantic feed (photo at right) shows that this particular pipe is 24" in diameter.

The size

of the pipe leading down to the Baltic is also contradicted by the Sanborn maps of

that facility, which list one 36" diameter pipe leading into the mill instead of a 38"

pipe reported in the other sources. In the original writing of this report, I was unable to

measure the baltic pipes because they were buried in snow. But on a trip back there in

October 1997 I was able to take the photo below. What I found was a diameter changing

fitting with a cleanout in the middle. The left side of the fitting measured 24", and the right side

measured 38" (both outside diameters)(31)

The steel dam, remarkable as it is, has features that separated it from the other

dams of it's type. For one, the dam was designed with a substantial concrete base

and a large angle from horizontal, depending on it's own weight and the weight of

the water to hold it in place. Also, unlike the other steel dams built, this one was

not built as a weir, or overflow dam, but instead used a spillway to deal with excess.

Here is a series of photos of this spillway.

weir1.jpg - The spillway nearing completion

weir2.jpg - The spillway during spring flooding in 1942.

The trestles shown starting from foreground are 1. to steel dam, 2. to Baltic Stamp mill (only one still

in existance), 3. overpass for roadway to Freda, 4. railroad trestle to mill along shore.

weir3.jpg - The gates to the spillway during a spring flood. As you

can see, water has already destroyed two of the wood sections.

gates1.jpg - The gate supports as they look present day. The

panels between them were removed in 1966.

NEW! bridgepilinginweir.jpg - Shot in early May 2002, this concrete pier is one of the supports for the trestles that crossed over the weir.

This spillway was 400

to 600 feet long (depending on which source you look at), 30 feet wide, 4 feet deep,

and 6 feet below the top level of the dam. This spillway was wrecked in the spring of

1905 and had to be completely rebuilt. A major question this author had when

researching the dam is why was the spillway built in the first place? The other two

steel dams built in that period were both overflow dams with no spillway. Unfortunately

no real information on this could be found, as the records from the firm that designed

the dam had either been lost or destroyed.(32) One guess would be that since the town

was directly downstream, the sound of water crashing down from 74 feet up would not

be welcome for any prolonged period. William Brinkman, in an article in the Daily Mining

Gazette, reported that when the dam overflowed in the spring of 1941 the roar could be

heard from his home in the village.(33) This may not be the case though, as photos of

the Hauser Dam in Montana (an overflow steel dam) show what appear to be dwellings

on one bank of the river.(34) Another

guess might be that although the engineers

designed it strong enough to survive overtopping, they did not want to risk it with such a

new dam technology. The risk would be that since this dam had a larger angle than the

other steel dams, the water would be falling much closer to the foundations, risking serious

undermining. The overtopping incident in 1941 came close to wiping out the road below the dam and convinced the

owners of the dam in 1943 to open the discharge valves at the foot of the dam as much as

possible. Other attempts were made in the 50's to open them further, but the valves had

been too rusted and jammed with debris. Even with the discharge valves open, the dam

again approached flood stage in the spring of 1976, this time it did not overflow, but the

trestles over the spillway were in serious danger of collapse, which would have torn the

road apart when the debris hit it. By 1979 the Copper Range Company, owners of the dam,

feared that the disrepair of the spillway would lead to a dam collapse. To eliminate the

possibility of that happening, the company cut 4 4' X 8' openings in the steel work just

above the concrete base. These holes can be seen in the photo at the beginning of this section.

Despite having little care since the mills it supplied water to closed down, the dam itself

is in rather good condition, but cutting the holes in the dam exposed the concrete below to

extremely harsh conditions  (water rapidly rushes over this area during spring thaw) and much

of the facing concrete there has crumbled away (photo at right). The dam has not had a use in over 70 years,

and yet it still stands as a testament to engineering know how in the early part of this century.

In 1985 a plaque was placed at the site listing it as a civil engineering landmark by the

Michigan section of the American Society of Civil Engineers (photo below).

(water rapidly rushes over this area during spring thaw) and much

of the facing concrete there has crumbled away (photo at right). The dam has not had a use in over 70 years,

and yet it still stands as a testament to engineering know how in the early part of this century.

In 1985 a plaque was placed at the site listing it as a civil engineering landmark by the

Michigan section of the American Society of Civil Engineers (photo below).

UPDATE: In May of 2002 I made another trip to Redridge to take photos. I felt I had to after reading on copperrange.org that the timber dam is in serious danger of being lost to us. To access the photos and commentary please click here.

This page hosted by  Get your own Free Home Page

Get your own Free Home Page

examination of the remains

of the Atlantic feed (photo at right) shows that this particular pipe is 24" in diameter.

The size

of the pipe leading down to the Baltic is also contradicted by the Sanborn maps of

that facility, which list one 36" diameter pipe leading into the mill instead of a 38"

pipe reported in the other sources. In the original writing of this report, I was unable to

measure the baltic pipes because they were buried in snow. But on a trip back there in

October 1997 I was able to take the photo below. What I found was a diameter changing

fitting with a cleanout in the middle. The left side of the fitting measured 24", and the right side

measured 38" (both outside diameters)

examination of the remains

of the Atlantic feed (photo at right) shows that this particular pipe is 24" in diameter.

The size

of the pipe leading down to the Baltic is also contradicted by the Sanborn maps of

that facility, which list one 36" diameter pipe leading into the mill instead of a 38"

pipe reported in the other sources. In the original writing of this report, I was unable to

measure the baltic pipes because they were buried in snow. But on a trip back there in

October 1997 I was able to take the photo below. What I found was a diameter changing

fitting with a cleanout in the middle. The left side of the fitting measured 24", and the right side

measured 38" (both outside diameters)

(water rapidly rushes over this area during spring thaw) and much

of the facing concrete there has crumbled away (photo at right). The dam has not had a use in over 70 years,

and yet it still stands as a testament to engineering know how in the early part of this century.

In 1985 a plaque was placed at the site listing it as a civil engineering landmark by the

Michigan section of the American Society of Civil Engineers (photo below).

(water rapidly rushes over this area during spring thaw) and much

of the facing concrete there has crumbled away (photo at right). The dam has not had a use in over 70 years,

and yet it still stands as a testament to engineering know how in the early part of this century.

In 1985 a plaque was placed at the site listing it as a civil engineering landmark by the

Michigan section of the American Society of Civil Engineers (photo below).