(Michael

Kammen, President of the Organization of American Historians

and a

member of the Smithsonian Council

during the Enola Gay controversy

cited in Linenthal and Engelhardt 60)

Bataan Perspectives:

Who's Bataan Death March

Remembering and Forgetting the Bataan Death March

in Textbooks

Miguel Llora

| Summary History textbooks are a primary vehicle for the transmission of dominant national narratives. Textbooks, however, contain an unstable set of social meanings that continuously change through political discourses. History textbooks are not the only shaper of a national narrative; war memorials that commemorate past heroic efforts are also mobilized in the production of a nationalist narrative. Memorials are important because of their appearance of permanence. The primary site of contestation for both the American and Filipino veterans is the old Camp O'Donnell site that is occupied by both the Camp O'Donnell Memorial and the Capas National Shrine. Both memorials at Camp O'Donnell are significant because they teach the public what is worth remembering about the Bataan Death March, yet they emphasize different perspectives. Finally, filmic representations matter because they enter our psyche unlike any other media. The portrayals of American staying power in films reminds viewers of righteousness, benevolence, and bravery. The marked absence of the Bataan Death March in Japanese and Filipino cinema is representative of a sense of victimhood and betrayal respectively. |

| Perspective: United States of America The contents of American history textbooks are therefore driven not by pedagogical goals and/or needs but rather by the political agendas of State Boards of Education, and informed by the ideological framework of the political constituency that voted for them. Howard Zinn and James Loewen argue that, driven by political and/or nationalist agendas, high school history textbooks either omit relevant information and/or transmit false ones (Loewen 1-7, Zinn 683, and Masalski 260). According to former High School teacher Kathleen Masalski, critics like Loewen go too far when they argue that history teachers don’t know much history, and that high school teachers uncritically utilize provided texts (Masalski 260). In K-12 public schools in the United States, a local school board decides which textbooks to use from a selection of books that have been vetted by the individual state’s Department of Education. Masalski used her textbooks because, “they offered me, as they do other teachers, a convenient means of organizing a course. They promised me the security of knowing I was “covering the waterfront” (as Loewen put it), that my students would not be disadvantaged on state or nationwide tests” (Masalski 260). Therefore, entries in U.S. textbooks selected below reflect the sentiments, knowledge basis, and epistemology of the times in which they were articulated. |

|

|

| In 1943, Atlantic Pictures released the film Corregidor,and Loew’s released the movie Bataan.Both the textbook entries and the filmic representations note “staying power” but are uncritical of how the exchange between MacArthur and Roosevelt lead to the desperation to begin with. On the one hand, Corregidor is an attempt by filmmakers to depict the goings on at MacArthur’s headquarters. Despite the lack of supplies and manpower, according to this narrative, the struggle selflessly continued. The filmmakers are vague in Corregidoras to why there were no supplies. Sacrifice in the film nonetheless situates the soldiers as heroic. | |

| On the other hand, Bataan is a purely fictive rendition of a troop of soldiers who delay the Japanese advance by blowing up a bridge. Although nervous and clumsy at first, the crew heroically joins together in time to get the job done. | |

| In 1945, RKO Radio Pictures released Back to Bataan, marking an effort by Hollywood to assist in establishing the “Good War” narrative . The release of the three movies and the textbook entry are an attempt to reverse the “expendability” narrative that came out of the Dyess report in 1942. In Back to Bataan, by playing up the post Leyte Gulf landing rescue missions to save soldiers from the Prisoner of War (POW) camp, Hollywood becomes the artistic arm of a society that needs closure and atonement. | |

| This narrative will be revisited many times beyond 1945 with the heroic depictions of the rescue at Cabanatuan,[a prison camp close to Camp O’Donnell. The portrayals of American resilience in films like Corregidor, Bataan, and Back to Bataanas well as textbook entries celebrate the “stiff measure of the staying power of the American nation” and reify notions of innocence, righteousness, benevolence, and bravery. In these immediate postwar narratives, Filipino involvement in Bataan and Corregidoris relegated to the sidelines. T. Fujitani argues, “In 1946 Congress refused to fulfill FDR’s promise to the 100,000 Filipino soldiers who had fought with U.S.troops that they would be allowed U.S.citizenship and veteran’s benefits” (241). Denial of Filipino participation haunted the U.S.throughout the decades beyond 1946. Filipino participation in textbooks, memorials, or any other venue, takes away from the full extent of American benevolence and sacrifice. |

|  |

|

|

|  |

|

|

| The Good War The Bataan Death March in textbooks, despite the shame of abandonment and loss and subsequent rescue re-articulates American righteousness and Japanese aggression. The narrative of the “Good War” paints the U.S.as an “innocent” nation fighting a “righteous” war (Linethal 61). First, textbooks entries made no reference to President Roosevelt and Secretary of War Stimson’s decision to redirect supplies and manpower to Europe, leaving the soldiers in Bataan and Corregidorill-equipped and starving. Second, entries that emphasize American suffering are problematic because the suffering is exaggerated and meant to be representative of the whole march when in fact it was not. Third, if any descriptions of suffering are given, they are portrayed as heroic and justified, presented a sign of “staying power” on the side of righteousness. Last, from entry to entry, the numbers change – with an emphasis of U.S. sacrifice and bravery (in reference to benevolence) often at the expense of accurately depicting Filipino participation in Bataan – all in an effort to maintain the notion that the Americans fought the “Good War” in textbooks and memorials. |

|

Perspective: Japan Evidenced by recent Japanese government "suggested" or "approved" alterations to the textbooks is the currently vogue practice by a string of Japanese governments to assuage Korean and Chinese concerns over what happened in World War II. However, the powerful common sense understanding is that the war was fought mainly between Japan and the U.S. The entry below alludes to an occupation of exploitation and ill treatment of other Asians but there is no mention of any particular event and conspicuous by its absence is any entry relating to the Bataan Death March. |

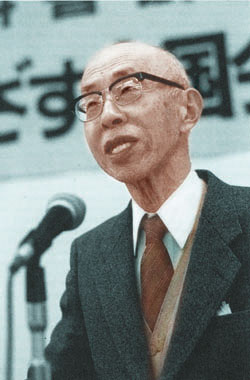

| Although

I was opposed to the war, I did nothing to resist, so it can be said that my battle

is one of resistance that came later. (Ienaga Saburo) Source: http://www.imdb.com/name/nm0406952/bio |

| State

of History Education in Japan Today: Fujioka Nobukatsu The Japanese Society for History Textbook Reform was established two years ago, by those of us who became deeply concerned by the very serious state of history education in Japan. Half-a-century has passed since the end of World War II, but this is the first time in over fifty years that we Japanese have begun to look at our own history with our own eyes, and make our own judgements. Our view of modern Japan's history, our perception of it, has been an amalgam of histories as understood and judged by the victors of the last war, namely the USA and the former USSR. This view was forced upon Japan after Japan's surrender, and was inevitable to some degree. The Japanese, on the one hand, submitted to the victors' view of history, while on the other hand chose not to think about it and rather pursue better living standards and a path to prosperity. Today, Japan has a well-developed economy and is in a position to make great contributions to world peace and prosperity, if she so chooses. However, I believe that our conventional historical self-perception is actually pulling us away from a sense of international responsibility and true integrity. I believe that if Japan is to share her wealth with other nations, then I would like to do it willingly, not grudgingly. Yet the past administrations of Japan seem to have a record of doing precisely this. The pattern seems to be, foreign government pressure, and giving in, and pressure, and giving in. That was how Japan cooperated in the Gulf War. Modern Japan seems to lack a strong self-image of what she is, what kind of country she wishes to become, what ideals she cherishes. These are all matters deeply related to the prevalent view of Japan's modern history, which I and my colleagues call the masochistic view. Source: http://www.jiyuu-shikan.org/e/education.html Existing textbooks, the book assumes, bad-mouth Japan, promoting a history of "self-abuse" that, as Fujioka baldly states in the introduction, "originates in the interests of foreign nations." History education, Fujioka argues, must benefit the Japanese state and should make Japanese "proud" of their nation again" (Gerow 74) |

|

|

|  |

|

|

|  |

|

|

|  |

|

|

|

|

|

There are more ideas on earth than intellectuals imagine. And these ideas are more active, stronger, more resistant, more passionate than "politicians" think. We have to be there at the birth of ideas, the bursting outward of their force: not in books expressing them, but in events manifesting this force, in struggles carried on around ideas, for or against them. Ideas do not rule the world. But it is because the world has ideas... that it is not passively ruled by those who are its leaders or those who would like to teach it, once and for all, what it must think. Michel Foucault |

[1] The Cabanatuan rescue was revisited with some historical grounding in Hampton Sides’ 2001 Ghost Soldiers: The Forgotten Epic of World War II’s Most Dramatic Mission, the resultant 2003 PBS documentary American Experience: Bataan Rescue: Death March and Rescue, and the 2005 John Dahl film The Great Raid.