====================================================================

by Guy Shaked

Keywords: Ben Naftali, Chinese Jews, Kaifeng, Section books, Shaked, Tiberian accents system

Abstract

The Hebrew manuscripts of the Jewish community of Kaifeng (China) contain accents. These accents are unique in that they serve a musical purpose and are less bound to grammatical functions as other accents are. Therefore, it could be deduced that in the Jewish community of Kaifeng operated a composer (or composers) or transcriber (or transcribers) of folk melodies (sort of pre-ethnomusicologist). He (or them) strove to use the Jewish Tiberian accents system as a mainly musical notation system.

Article

In 1994 I came across the manuscripts of the Jewish community of Kaifeng, which contained accents [1]. The careful study of these accents, which, to my knowledge, were not researched before, has shown them to be a unique example of accents which function specifically as musical formulas, liberated from their hierarchical grammatical function.

Until now all accents found in Jewish manuscripts serve also a grammatical hierarchical function.

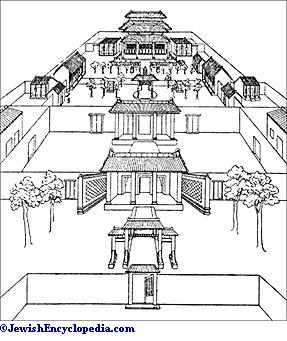

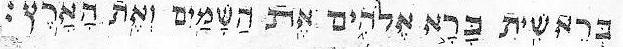

The first such manuscript to be presented here in which these "grammatically free" musical accents appear is the Prayers book from Kaifeng (Fig. 1)

As far as is known these three poems are unique to the Kaifeng manuscripts and do not appear outside of these manuscripts.

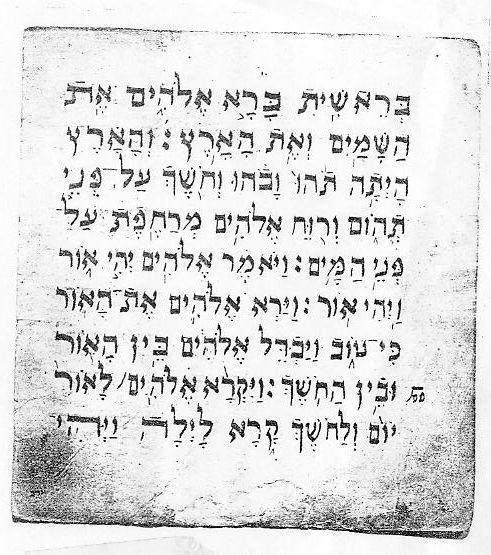

Yet there is another widespread example of these musical accents in the Section Books of the Torah from Kaifeng. These contain a version of the Teberian Accents System.

Although the Masoretic accent tradition in the Section books follows closely the Tiberian accent system, it contains slight but meaningful differences.

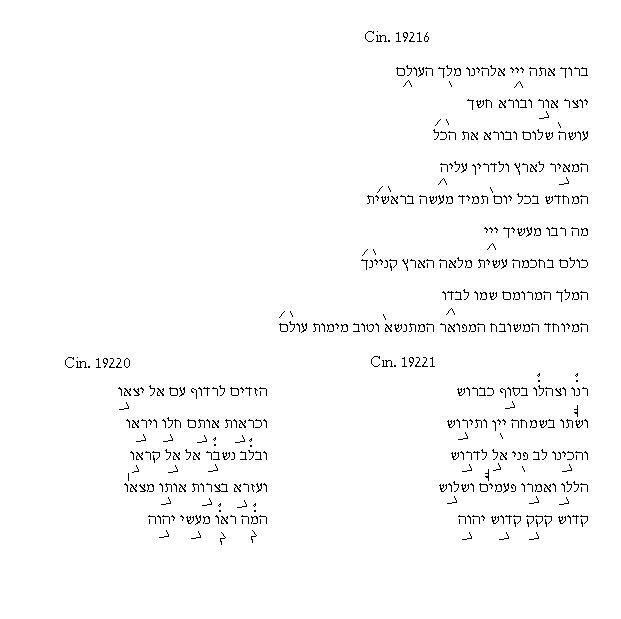

Fig. 2 The Bereshit Section book (Genesis 1:1-6:8) from Kaifeng (Chinese Library, Royal Ontario Museum)

A comparison between the Masoretic accents in the Section books of the Torah from Kaifeng and the Tiberian accent system reveals one main systematic structural difference: diffusion between Tipeha and Merkha and Sof-Pasuk

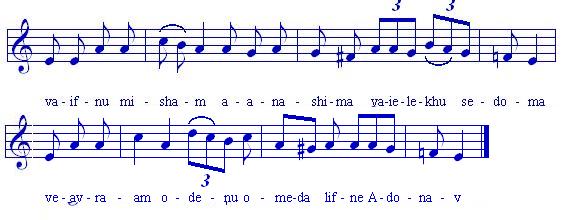

Ben-Asher and Ben-Naftali introduced several interchanges of Tipeha and Merkha [2]. In the Section books from Kaifeng, these signs become interchangeable in many cases, and lose major aspect of their grammatical function (Fig. 3).

Fig. 3 Diffusion between Tipeha and Merkha in the Bereshit Section book, compared to the Tiberian accent system

In figure 3, the Merkha on the word "hashamaim" becomes identical to the Tipeha in its shape.

As a result of this main systematic structural difference, the accent system in the Kaifeng Section Books is simpler than the Tiberian accent system, as it contains fewer hierarchical verse subdivisions than the Tiberian accent system. In the Section books, one main recurrent accent (which might be named "the stem") dominates the text (in Fig. 3 the stem appears 39 times, which equals the presence of all other accents). So that in the Kaifeng Section Books those three accents lose their hierarchical grammatical function as sub dividers of the phrases. Retaining perhaps a simpler melodic significance as a returning musical formula/note.

The question remains whether these "grammatically free" accents, which served therefore a mainly musical function, were the product of Chinese Jewish culture or arrived to China with some manuscripts the product of a community outside China.

The answer to this question lays with the unique shape of some of the accents in the Kaifeng manuscripts.

For example the accent name appears to have been changed in shape in the Kaifeng manuscripts under Chinese cultural influence [3]. It's shape has been made to look more like the Chinese letter name, shape, place in the Kaifeng manuscripts, it could be said to have been "Chinaized".

This change of shape might hint to an assimilated musical function of the accent, because the letter name was also used to denote the musical note name on the Chinese instrument name for example.

So it seems that the accents in the Kaifeng manuscripts with their unique shapes at some cases were modified and given new function under a Chinese cultural influence. Their uniqueness, therefore, because of its connection to the Chinese language, belongs to that environment and is not an imported feature.

Another question remains: was the music notated in the Kaifeng manuscripts originally composed music or were the tunes folk music of the community that were orally transmitted from one generation to another. Regarding the Section Books of the Torah from Kaifeng some conclusion can be reached. For they contain melodically simpler chant system of signs than the Tiberian accents system.

The Tiberian accent system is a grammatical and phonetic system of signs. These signs serve to divide the text into hierarchical parts (text, verses, sub-verse units, phonemes) and clarify the correct pronunciation of words and the exact stress of each word. They also assist in understanding the difficult, sometimes ambiguous, words and the state of mind expressed in the text (question, puzzle, shout, etc.).

Several ethnomusicologists claim that present day Torah chant practice in most Jewish communities (except the Ashkenazi) differs from the written Tiberian (Masoretic) accent tradition.

For example, Leo Levi, an ethnomusicologist who specialized in Italian Jewish music, stated in 1971:

In this tradition, only five or six of the main (disjunctive) accents are rendered by musical motives of their own. The application of the motives does not coincide with the Tiberian accentuation system with which the biblical text is provided, implying the existence of an independent system based on an oral tradition [4]. Levišs transcription of the reading of the Torah according to Italian rite (Fig. 4), shows how the Zakef Gadol accent receives two distinct musical formulas.

Fig. 4 Italian rite, reading the Torah [play]

Such scholars as Abraham Z. Idelsohn, Uri Sharvit and Avigdor Herzog, who researched the chant of other Jewish communities, among which the Yemenite, Persian, Daghestani and Kurdish, agreed that the oral system differs from the written Tiberian system [5].

For example, Idelsohn's transcription of the Torah reading according to the Daghestani tradition (Fig. 5) demonstrates that the Daghestani oral tradition reflects only the two main syntactical units of the text.

Fig. 5 Daghestani tradition, reading the Torah [play] [4]

The study of these scholars demonstrates tat in most Jewish communities there was a simpler oral hierarchically chant system than the written Tiberian system. This is also the case in the "modified" written chant system in the Kaifeng Section Books of the Torah. Suggesting, that the written chant system in the Kaifeng Section Books, was possibly modified according to the community's simpler oral tradition of chant. This suggests, that it is possible that the transcriber/s of Kaifeng was/were writing down folk music (transcribing) in a similar way to that which modern ethnomusicologist do.

He was (or they were) using the Tiberian accents system's various signs as musical notation to compose or notate perhaps folk music in a mode maybe similar to modern ethnomusicologists.

His work might be of the 1620's, as the Section Books of the Torah, and their colophons indicate that they were written in Kaifeng in the 1620s. Most scholars agree that Jewish communities emerged in China around the 12th century [7].

Hear Psalm 122 performed to the Author's Music

Read more of Guy's work in the book: Masters of Italian Sculpture

Read more of Guy's work in the book: Masters of Italian Sculpture

-----------------------------------------------

[1] The vast majority of manuscripts of the Chinese Jewish community of Kaifeng are preserved in the HUC Cincinnati library collection. The rest of the manuscripts are kept in various other libraries in the U.S.A. Canada and the U.K.

[2] Aaron Dotan, "Sefer dikdukey ha-teamim: Le-rabi Aharon Ben-Moshe Ben-Asher" (Ph.D. diss., The Hebrew University, Jerusalem, 1963), 236

[3] Guy Shaked, "The Shapes of the Masoretic Accents in Kaifeng's Manuscripts", Points East, 11/22 (1996): 5

[4] Leo Levi, "Italy : Musical Tradition", EncJud 9:1145

[5] Abraham. Z. Idelsohn, "Songs of the Jews of Persia, Bukhara and Daghestan", Thesaurus of Hebrew Oriental melodies : Hebraeisch-Orientalischer Melodienschatz 3 (n.p.:Ktav, 1973) 21,36-8; Uri Sharvit, "Introduction: Yemenite-Jewish Tunes: Their structure and manner of performance", in Yehiel Adaqi & Uri Sharvit eds., A treasury of Yemenite Jewish Chants, ([Jerusalem] : Israeli Institute for Sacred Music, 1981) xxv-xxvi; Avigdor Herzog, "Masoretic Accents," EncJud 11:1100

[6] Idelsohn, "Neginot", 67,n.170

[7] Joseph Deherenge and Donald D. Leslie, Juifs de Chine (Roma : Institutum Historicum S. I. : Paris : Les Belles Lettres, 1980), 9-15; Michael Pollak, Mandarins, Jews, and Missionaries (Philsdelphia : Jewish Publication Society of America, 1980), 255-273; Donald D. Leslie, The Survival of the Chinese Jews (Leiden : E.J.Brill, 1972), 22-24

Regarding this article:

| NAME & PLACE | COMMENT |

| - | Cited by 1 academic article (previous version of this article) |

Dear visitor, please take a short moment to sign my guest book!

Hear Psalm 122 by the author in the background of photos of Jerusalem from

www.JerusalemShots.com

----------------------------------------------------------------

© 2004, 2007 (2nd ed.) Emails are

gladly received: shakedtg@hotmail.com

The harp as a hidden symbol in Bernini's 'David'

Other articles by G. Shaked:

ART

BIBLICAL STUDIES

BIOLOGY

CINEMA

LITERATURE

MUSIC

PHILOSOPHY

PHYSICS

(ACOUSTICS)